He’s one of the most famous humans who has ever lived — even though he’s not that cute, not that smart and not that great a soccer player

By Mark Simpson

(Originally appeared on Salon, June 28, 2003)

It hasn’t been like this since the death of Diana. Britain has been suffering from a national nervous breakdown ever since David Beckham, handsome icon of the Manchester United soccer team, announced last week that he was leaving to play for Real Madrid.

The Sun, the best-selling UK tabloid, set up a Beckham “grief helpline” and claims it has been swamped with calls from distressed fans. One caller said he was considering suicide, while several confessed that they were so upset they couldn’t perform in bed. A man who has “Beckham” tattooed on his arm threatened to cut if off. “I cried myself to sleep after hearing the awful news,” said grandmother Mary Richards, age 85. A London cabby, ever the voice of reason, asked, “Has the world gone mad? He’s only a footballer!” But he was mistaken. A footballer is now the least of what David Beckham is.

In the era of soccer that will come to be known as B.B. – Before Beckham – the sport was a team game. What mattered was the club, the team and the player in that order. Then in the mid-1990s, David Beckham — or “Becks” as he is known in that familiar, affectionately foreshortened form with which the British like to address their working-class heroes — came along, flicked his (then) Diana-style blond fringe and changed the face of soccer. It wasn’t his legendary right foot that altered the game, but his photogenic face — and the fact that he used it to become one of the most recognizable, richest and valuable athletes in the world, receiving a salary of $8 million per year, earning at least $17 million more in endorsements and commanding a record transfer fee for his move to Real Madrid of $41.6 million.

Beckham’s greatest value is his crossover appeal – he interests not only those who have no interest in the club for which he plays, but those who have no interest in soccer. He is the most recognized sportsman in Asia, where soccer is still relatively new. Possibly only Buddha himself is better known – though Beckham is catching up there too: In Thailand someone has already fashioned a golden “Becks” Buddha. He’s even managed to interest Americans, for God’s sakes. The 27-year-old, tongue-tied, surprisingly shy working-class boy from London’s East End has succeeded in turning the mass, global sport of soccer into a mass, global promotional vehicle for himself, reproducing his image in countless countries. He has turned himself into a soccer virus, one that has infected the media, replicating him everywhere, all over the world, endlessly, making him one of the most famous men that has ever lived.

David Beckham, in other words, is a superbrand.

In recognition of this, Becks was the first footballer ever to receive “image rights” — payment for the earning potential his image provided his club — and got them, to the tune of $33,300 a week. In fact, image rights were the main issue at stake in the record-busting six weeks of contract renegotiations he had with Manchester United last year; his worth as a player was agreed at $116,500 a week almost immediately. Then there’s that $17 million a year for endorsing such brands as Castrol, Brylcreem, Coca Cola, Vodafone, Marks & Spencer and Adidas. And Becks just keeps getting bigger. His trusty lawyers have already registered his name for products as various as perfumes, deodorants, jewelry, purses, dolls and, oh yes, soccer jerseys. Such is the power of the Beckham brand that it’s hoped it can rescue the fortunes of Marks & Spencer’s clothing (a high-end British chain that has become a byword for “dowdy”).

But alas, the brand couldn’t save murdered Suffolk girls Holly and Jessica, poignantly pictured last year in police posters in matching replicas of his No. 7 red shirt. When it was still hoped that they might be runaways, the man himself made a broadcast appeal for their return. There was the Becks, eerily right at the heart of the nation’s hopes and fears again.

Beckham has even managed to brand a numeral – 7 – the number on his soccer jersey. A clause in his Manchester United contract guaranteed him No. 7, he has 7 tattooed in Roman numerals on his right forearm, his black Ferrari’s registration plate is “D7 DVB,” and his Marks and Spencer’s clothing line is branded “DB07.” He even queues at No. 7 checkout when he goes shopping. This is often interpreted as a sign of his superstitiousness but is more an indication of his very rational grasp of the magic of branding. (He may, however, have to settle for the number 77 when he moves to Real Madrid, as the coveted 7 is already taken by Spanish superstar Raul.)

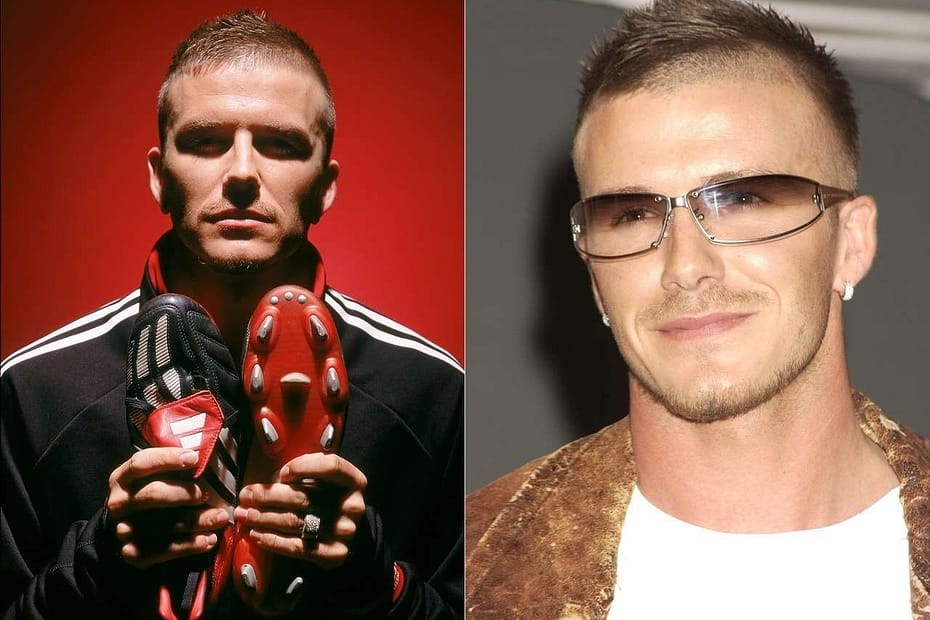

But somehow, Beckham has not yet become a victim of his own success and has managed to remain officially “cool.” Europe’s largest survey into “cool” recently found that Beckham was the “coolest” male, according to both young women and men. Beckham’s status can be attributed to his diva-esque versatility and his superbrand power: “Like Madonna he is very versatile and able to radically change his image but not alienate his audience,” says professor Carl Rohde, head of the Dutch “cool hunting” firm Signs of the Time. “He remains authentic.” Each time he goes to the hairdresser’s and has a restyle – which is alarmingly often – he ends up on the cover of every tabloid in Britain. In other words, whatever Becks does, however he wears his hair or his clothes – or, crucially, whatever product he endorses – he is saying, as Rohde puts it, “this is just another aspect of me, David Beckham. Please love me.” And, it goes without saying, buy me. And millions do.

Becks’ greatest sales success, however, was actually on the football field – though less with the ball than with the camera. He’s the most famous footballer in the world, and considered by millions to be one of the greatest footballers of all time, but arguably he’s not even a world-class player. A very fine one, to be sure, but not nearly the footballer we are supposed to think he is — not nearly the footballer we want to think he is. Sport, you might imagine, is the one area of contemporary life where hype can’t win, where results, at the end of the day, are everything. But Beckham has disproved that, has vanquished that, and represents the triumph of P.R. over … well, everything. His contribution to Manchester United was debatable. On footballing skills alone, he is arguably not worthy of playing for the English national team, let alone being its captain. However, in the last decade soccer has become part of show business and advertising.

Beckham is a hybrid of pop music and football, the Spice Girl of soccer – hence his marriage to one. He is – indisputably – the captain of a new generation of photogenic, pop-tastic young footballing laddies that added boy-band value to the merchandising and media profile of soccer clubs in the 1990s.

Beckham’s footballing forte is free kicks. This is entirely appropriate, since these are, after all, among the most individualistic – and aesthetic – moments in soccer. Unlike a goal, with a free kick there’s no one passing to you, no one to share the glory with. Instead there’s practically a spotlight and a drum roll. And how he kicks! “Goldenballs” (as his wife, Victoria, aka Posh Spice, reportedly likes to call him) has impressive accuracy and his range is breathtaking – along with his famous “bending” trajectory, his kicks also have style and grace. Long arms outstretched à la Fred Astaire, wrists bent delicately upward, forward leg angled, and then – contact – and a powerful, precise, elegant thwump! and follow-through.

An Englishman shouldn’t kick a ball like this. This is the way that Latins kick the ball. Beckham doesn’t just represent the aestheticization of soccer that has occurred in a media-tised world – he is the aestheticization of it. Like his silly hairdos, like his “arty” tattoos, like the extraordinarily elaborate post-goal celebrations he practices with the crowd, almost everything he does on the field is designed to remind you that No. 7 is anything but a number.

Off the soccer field Becks is able to use clothes and accessories to draw attention to himself. And does he. The Versace suits, the sarong, and the sequined track suit that opened the Commonwealth Games dazzled TV audiences and confused some foreign viewers who still thought the queen of England was a middle-aged woman. Essentially, Beckham’s visual style is “glam” – more Suede than Oasis (with a bit of contemporary R&B pop promo thrown in). And like glam rock, which was a British working-class style running riot in the decade of his birth, the 1970s, Beckham, the son of Leytonstone proletarians, has a clear image of himself as working-class royalty, the new People’s Princess (though his “superbrand” power has as yet been unable to sell us his wife, who, post-Spice Girls, remains unpopular and unsuccessful). Hence his wedding took place in a castle; at the reception afterward Posh and Becks were ensconced in matching His ‘n’ Hers thrones, and their Hertfordshire home was dubbed “Beckingham Palace” by the tabloids.

Soccer, like pop music, is one of the few ways the British are permitted any success — it is, after all, something both manual and aristocratic at the same time. Becks the football pop star represents and advertises a materialistic aspirationalism that doesn’t appear bourgeois.

Beckham’s tattoos – a literal form of branding – seem to epitomize this. What were once badges of male working-class identity are now ways of advertising the unique Becks brand. “Although it hurts to have them done, they’re there forever and so are the feelings behind them,” Becks has explained. But these are not the kind of “Mum & Dad Always” tattoos his plumber dad and his mates might have had. The huge, shaven-headed, open-armed, “guardian angel” with an alarmingly well-packed loincloth on his back looks more than a little like himself with a Jesus complex. Beneath, in gothic lettering, is his son’s name: Brooklyn. Once his uniform comes off at the end of a match – as it usually does, and before anyone else’s – the tattoos help him to stand out instantly, and mean that he is never naked: He’s always wearing something designer.

Becks clearly enjoys getting his tits out for the lads and lasses — and oiling them up for the cover of Esquire and other laddie mags. While he may look strangely undernourished and fragile in a soccer uniform, as if his ghoulishly skinny wife has been taking away his fries, and all those injuries suggest he’s somewhat brittle, stripped down he looks as lithe and strong as a panther. He doesn’t drink, he doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t do drugs. His body is a temple — to his own self-image — which he never ceases worshipping.

There is however a submissive photophilia to Becks. A certain passivity or even masochism about his displays for the camera, which seem to say “I’m here for you.” Hence perhaps the fondness for those Christ-like/James Dean-like poses with arms outstretched (the cover of Esquire had him “crucified” on the Cross of St. George). Even those free kicks seem to have the loping iconography of “Giant” or Calvary about them. Truth be told, Becks is there for him, but it’s a nice thought nonetheless.

To some he is already a god – literally. In addition to the Thai Becks Buddha, a pair of Indian artists have painted him as Shiva, the Hindu god of destruction. In the Far East, androgyny is seen as a feature of godhead – and so it has here in the West as well since the Rolling Stones. As Becks tells us himself: “I’m not scared of my feminine side and I think quite a lot of the things I do come from that side of my character. People have pointed that out as if it’s a criticism, but it doesn’t bother me.” It’s as if when he was a teenager he looked at those grainy black-and-white ’80s girlish bedroom shrine posters of smooth-skinned doe-ish male models holding babies and thought: I’d like to be like that when I grow up. Becks is the poster boy of what I have termed elsewhere metrosexuality.

His hero/role-model status combined with his out-of-the-closet narcissism and love of shopping and fashion and apparent indifference to being thought of as “faggoty” means that for corporations he is a pricelessly potent vector for persuading millions, if not billions, of young men around the world to express themselves “fearlessly,” to be “individuals” – by wearing exactly what he wears. Beckham is the über-metrosexual, not just because he rams metrosexuality down the throats of those men churlish enough to remain retrosexual and refuse to pluck their eyebrows, but also because he is a sportsman, a man of substance – a “real” man – who wishes to disappear into surface-ness in order to become ubiquitous – to become me-dia. Becks is The One, and slightly better looking than Keanu – but, be warned, he’s working for the Matrix.

Ultimately, though, it is his desire that makes him the superbrand that he is. Beckham has succeeded where previous British soccer heroes you’ve never heard of, such as George Best, Alan Shearer and Eric Cantona – a Frenchman who played for Manchester United and is John the Baptist to Beck’s Christ – have failed, and has become a truly global star. Partly because the world has changed but mostly because they didn’t want it as much as he did. Becks is transparently so much more needy – more needy than almost any of us is. The public, quite rightly, only lets itself love completely those who clearly depend on that love, because they don’t want to be rejected. Beckham’s neediness is literally bottomless. Like his image, it grows with what it feeds on. He’ll never reject our gaze.

It’s there in his hungry face. He isn’t actually that attractive. Blasphemy! No really, his face doesn’t have a proper symmetry. His mouth is froglike and bashfully off-center. But what is attractive, or at least hypnotizing in a democratic kinda way, which is to say mediagenic, is his neurotic-but-ordinary desire to be beautiful, and to use all the technology and voodoo of consumer culture and fame to achieve this. His apparent lack of an inner life, his submissive, high-pitched 14-year-old-boy voice that no one listens to, his beguiling blankness, only emphasize his success, his powerfulness in a world of superficiality. That oddly flat-but-friendly gaze that peers out from billboards and behind Police sunglasses looks to millions like the nearest thing to godliness in a godless world. People fall in love not with him – who knows what Beckham is really like, or cares – but with his multimedia neediness, his transmitted “viral” desire, which seems to spread and replicate itself everywhere, endorsing multiple products. Becks’ desire, via the giant shared toilet handle of advertising, infects us, inhabits us and becomes our own.

The British for their part, even those calling tabloid papers in tears to declare their lives ruined now that Beckham is moving to Real Madrid, will survive sharing him with the Spanish for a few years. After all, they’re already proudly sharing him with most of the rest of the world – and basking in his reflected glory. No one buys our pop music anymore; our “Britpop” prime minister, Tony Blair, post-Iraq, is widely regarded abroad as a scoundrel; our royals, post Diana, are a dreary bunch of sods (even her sainted son William is beginning to lose some of his Spencer spark and glow to the tired, horsey blood of his “German” dad and grandmama); and our national soccer squad has difficulty beating countries with a population smaller than Southampton.

But “our Becks” on the other, perfectly manicured hand, is something British the world seems to actually want. Badly.