On the 55th anniversary of the NYC bar riot at which everyone over 75 now claims they threw the first bottle, I thought I would post this piece about the expiration of gay bohemianism in the 1980s. More a series of not terribly well-integrated notes than essay, it was originally published in Arena Hommes Plus, in 2009. It hasn’t been made available online previously.

———

Sometimes love is literally throwing yourself at a concrete wall.

Eija-Riiita Berliner-Mauer married the Wall in 1979 (her surname means ‘Berlin Wall’ in German). When much of the Wall was torn down a decade later in 1989 amidst scenes of jubilation, its wife was aghast. “What they did was awful” she complained. “They mutilated my husband.”

Inevitably, Mrs Berliner-Mauer’s story has provoked anger, ridicule, and voyeuristic sympathy, but I wonder though whether her love is really so strange. I wonder whether many of us don’t secretly love the Berlin Wall a bit too, now it’s gone – or the Anti-Fascist Protective Rampart to give it its proper, East German Doublespeak name.

I’m sure I do. But then I had a childish desire to be caught up in that drama that as a teenager I sometimes fantasised about calling up the East German embassy – it had to be East Germany because East Berlin was always where the spies went in the movies – and offering to work for them, knowing full well that the line would be tapped by Our Side. And that the East Germans would have no use for me.

Or maybe it was just because I fancied Rupert Everett’s pretty blond boyfriend (Cary Elwes) in early 80s gay traitor flick, Another Country. It is difficult to even conceive of it now, but gay traitors were the height of cool in the 80s – the cocktail bar in Manchester’s legendary Hacienda nightclub was called ‘The Gay Traitor’.

Either way, like Mrs Berliner-Mauer I’ve never quite recovered from the ‘mutilation’ of her husband, and the collapse of the world that it symbolised.

But then, it’s quite apparent that Western Civilization hasn’t either.

——–

1989 wasn’t just the year of the last great New Order album, but also the end of the twentieth century. Centuries, like decades and celebrities, are not very punctual. Though at least the 80s had the decency to be a decade long: beginning in 1979 with the election of Margaret Thatcher as UK PM and the release of Ridley Scott’s Alien and ending in November 1989 with the dismantling of the Wall, and with it the most heroic and appalling century in human history.

History, as Marx liked to point out is full of paradoxical effects. And one of the peculiarly paradoxical effects of the collapse of that dystopian symbol was… the end of utopianism. Whatever you thought of ‘Actual Existing Socialism’ as it was called in the East, it represented by its Actual Existence the very possibility of an ‘alternative’. You just had to get the fine print right (which is why there were so many leftist splinter groups in the West – all arguing over that fine print). After 1989 there really was, as Maggie Thatcher had told us, no alternative. The Left as a whole collapsed with the Berlin Wall, like so much badly cast concrete, regardless of how critical it was of Moscow or Marxism.

The odd thing about the divided, mobilized-not-mobile-owning, Walled-not-wired world of the 1980s was that, in London at least, amidst the smoking ruins of the Welfare State and social democracy, it allowed you to live in your own New Jerusalem – even if you weren’t actually very political; and most of the queer boys with a passion for fashion were not. While Moscow and Washington faced off, we were all able to dream and scheme and kid ourselves that we could live forever in squats with no visible means of support – or visible connection to reality. ‘Alternative’ back then was a fare-and-soap dodging way of life, not just an iTunes category.

It also happened to be bloody brilliant. London in the 1980s was a melting pot of the best of, largely American-inspired, pop culture, filtered and repackaged through the British experience – rockabillies, psychobillies, punks, skinheads, New Romantics, rude-boys, soul-boys – often with a leftist or leftist-styled politics. You really could have it both ways. And thousands of Provincial refugees – many of them queer boys with a passion for fashion – did. Filling the Hard To Let housing stock of the capital of Airstrip One with their treasured record collections and back issues of The Face and ID, hauled to London from Coventry on National Express. Gay or straight, there was a culture of sexual, social and political experimentation.

Mark Simpson’s Subby is reader-supported. To receive new posts, become a subscriber.

Subscribed

But fin de siècle has to fin. That ‘alternative’, Twentieth Century decadent world also came to an ugly end in the late 80s early 90s. In large part because so many of the brightest and the best of that generation hit another famous wall with graffiti scrawled across it in big scary – and back then capital – letters. AIDS.

This was the final, bloody victory of Thatcherism and Reaganism – holding a pneumocystis pneumonia pillow over the KS-scarred face of the emaciated, gasping, beautifully decadent Twentieth Century.

1989 was the year that London zeitgeist stylist, fashion propagandist and founder of Buffalo Ray Petri died from an Aids-related illness at the age of just 41. On the other side of the Atlantic, fearlessly iconoclastic photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s T-Cells also threw in the towel. The artist Keith Haring expired the following year, from the same fatal acronym. Terrifyingly talented UK performance artist and shape-shifter Leigh Bowery, and the experimental, militantly bohemian, but always utterly charming, film director and painter Derek Jarman persisted until 1994.

With no effective anti-HIV drugs available, the end of the 80s and the early 90s was a killing zone much more lethal than the Berlin Wall. By the time the protease inhibitors cavalry arrived in the mid-90s, it was, in a cultural sense, already too late. As if in sympathy, 1989 was also the year that the best, most stylish, most aristocratic gay diva of the Twentieth Century, Bette Davis, also decided to bow out.

Gay bohemianism, in many ways the artistic sensibility of the Twentieth Century and the muse of so much of the best of pop culture, was as dead as the century itself. The pope of gay pop cultural bohemianism, Andy Warhol, ever the trend-setter, quit in 1987 – the same year as Liberace, though not from Aids. The better part of an entire generation of ‘artistic’ boys were wiped out. Liquidated. Aids was a drawn-out St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre for gay bohemians. HIV was a thoroughly petit bourgeois virus: nasty, small-minded – but very, very efficient. (After gays, I/V drug-users, that other group of deviants, were its favourite target.)

The course of pop culture had been changed forever – by a bloodbath. And as a reminder of this great victory for conservatism, a greater one in some ways than the one achieved over Bolshevism, while the Berlin Wall was torn down, another formidable wall was erected, one which is still patrolled to this today. This Protective Rampart divided not East and West, but ‘Gay’ and ‘Straight’. The horrible, humiliating deaths of so many gay bohemians hadn’t just robbed the world of a generation of bright young things, it had proved highly instructive to the survivors. A harrowing, cowing example to everyone, whatever their sexuality, of the importance of respecting Nature’s law of demographics and the imperative need for focus groups, business plans, and property portfolios. In other words: Security.

‘Gay’ which had once meant Studio 54, Jean Genet, Ziggy Stardust, Christopher Isherwood, following your own light, and unconventional, cocktails at the Hacienda – now meant: High Risk. Disease. Horror. Squalor. Failure. Slow death. And – most terrifying and damning of all to the Twenty First Century – Niche. As the popular joke at the time had it: ‘Got Aids Yet?’

It was around the late 80s and early 90s that the word ‘gay’ began to be used in the argot of the new generation of illiterates raised by Thatcherism to mean ‘lame’. Engels once described the choice facing Western Civilization as socialism or barbarism: in the 90s, British pop culture chose barbarism. But it called it ‘New Lad’. Anything interesting, anything creative, anything artistic or sophisticated was now ‘too gay’, an expression which in the past would have meant ‘too cool’. ‘Too gay’ remains to this day the Pavlovian response of corporate half-men who live in fear of anything actually alive. Now that the working class had been eliminated politically, the metropolitan middle classes fetishised working class-ness and the very aspects of prole culture that so many working class boys and girls, gay and straight, had run away to the big city from (In the immortal words of Sheffield arty-farty working class straight boy Mr Cocker: ‘…we dance and drink and screw/because there’s nothing else to do’).

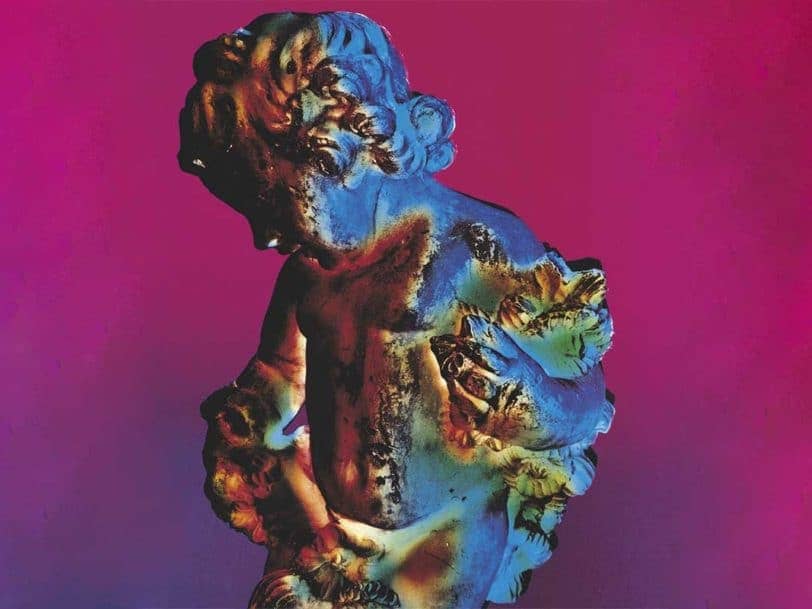

The kinds of broodingly iconic and knowingly, playfully homoerotic magazine covers that people like Ray Petri had pioneered in the 80s were now inconceivable. Gender Benders like Marilyn on the cover? You’re ‘avin a larf! In the 90s, pretty much everyone, with the exception of Brett Anderson, was painfully straight acting – especially those who were actually straight. Even more so if they were expensively educated. And it was largely down to Aids and the long, long list of gay bohemians Missing in Action and the sheer, emasculating terror it provoked in an entire generation.

It’s somewhat ironic, given the way that stylists have ruined the Twenty First century by becoming the style Stasi, making pop videos and in fact bands themselves unbearable because of their blandly ‘professional’ look, and giving all male celebs the same annoying Soho Beards, that Ray Petri should have been a stylist himself. But Petri was one of the very first, which is always its own alibi – especially when you’re actually avant-garde too. His work for The Face and ID was nothing short of historic – those propagandistic covers are still hauntingly powerful all these years on and look now like an accusation aimed at what came after. He can be forgiven for discovering Levis striptease artist and later pop singer Nick Kamen, kick-starting his career by putting him on the cover of The Face: being a himbo was a new, radical even, idea back then. And Kamen was devilishly, duskily, pretty. (Petri’s warm appreciation of non-whiteness was also something of a new idea for most magazines.)

Photographer and former Petri associate Jean-Baptiste Mondino told the NYT a couple of years back: “Petri was obsessed with ‘bad boys’, Jamaican culture and Native American imagery, and was always surrounded by a crowd of beautiful people. It was a true collective – in a way it reminded me of the Surrealist movement, but everyone was cool and relaxed. We would sit around listening to music, smoking a joint, and ideas would just come to us.” Neneh Cherry, penned the hit single Buffalo Stance (1988) about her friend Petri: ‘Who’s looking good today?/Who’s looking good in every way?’ she sang. Adding: ‘No moneyman can win my love/It’s sweetness that I’m thinking of.’

But sweetness had turned to sickness. Diagnosed with Aids in the late 80s, Petri refused to stay at home and still attended fashion shows. His bravery at a time when there was near-panic about Aids and paranoia about how it could be transmitted (another reason why Princess Di really was a princess), impressed Jean Paul Gaultier – himself one of the few enduring free spirits of that era – who always reserved a front row seat for him, at a time when many people with HIV were shunned, even in the fashion industry.

After his death, most everyone else in fashion got on with the business of making money. It was the David Bowie ‘Let’s Dance’ moment, which actually looks nowadays seriously avant-garde: but then, it sorta was: Bowie saw where the 80s were headed before anyone else who wasn’t actually in Thatcher’s Cabinet.

As Mondino has said: “I often think of what it would be like to have him around. Ray died just as fashion was becoming more commercial, but I don’t think that he would have approached things any differently than he always did. Most of his friends have made some money over the years, but to tell you the truth, we get a little bored a lot of the time.”

Yes, I really miss the twentieth century and its gay bohemians, and avant-gardists too.