How the Austrian Cinders became a Hollywood Prince

Two decades ago, during peak metrosexmania in the US, the bodybuilder movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger, never exactly shy about drawing attention to himself – and now running for office – briefly came out as metrosexual. Or at least, welcomed the tag being applied to him. As the ‘father’ of the metrosexual, I was asked in one of the many media interviews I did at the time whether I agreed that the Austrian Oak fitted the description. This was my answer:

Yes… but not, as has been suggested, because he wears Prada shoes. As a multimillionaire film star, what else is he supposed to wear?

Rather, Arnie is an example of early metrosexuality, proto-metro… after watching too many Steve Reeves movies as a boy, he became devoted to his physique, turning himself into a spectacle, a sign, a commodity, one that was eventually noticed and bought by Hollywood – and used to seduce hundreds of millions of other boys around the world into turning themselves into commodities. This is the new American Dream: Don’t live it, become it. Arnie was a new kind of working-class hero, one who works on himself, not on his boss’ property – labouring for aesthetics.

In fact, I was wrong. About Steve Reeves. As the new, fawning, full-access Netflix doc Arnold shows, it was the square-jawed, highly handsome English bodybuilder and three times Mr Universe Reg Park (1928-2007) playing Hercules in a sword and sandal movie that was the early, glistening love-object and inspiration for the ambitious Austrian.

But I was right about everything else.

The documentary is divided into three parts, ‘Athlete’, dealing with his childhood and bodybuilding career, ‘Actor’, chronicling his Hollywood years, and ‘American’, about his political career. I was much more interested in the ‘Athlete’ episode than the ‘Actor’ episode, and not very interested at all in the ‘American’ episode, which seemed to be mostly cringe clips of him delivering uber-cheesy reworked Terminator catchphrases at political rallies with a shit-eating grin. (He served as ‘Governator’ of California for two terms, from 2003-2011 – nominally as a Republican, but really as the leader of the Arnie Party).

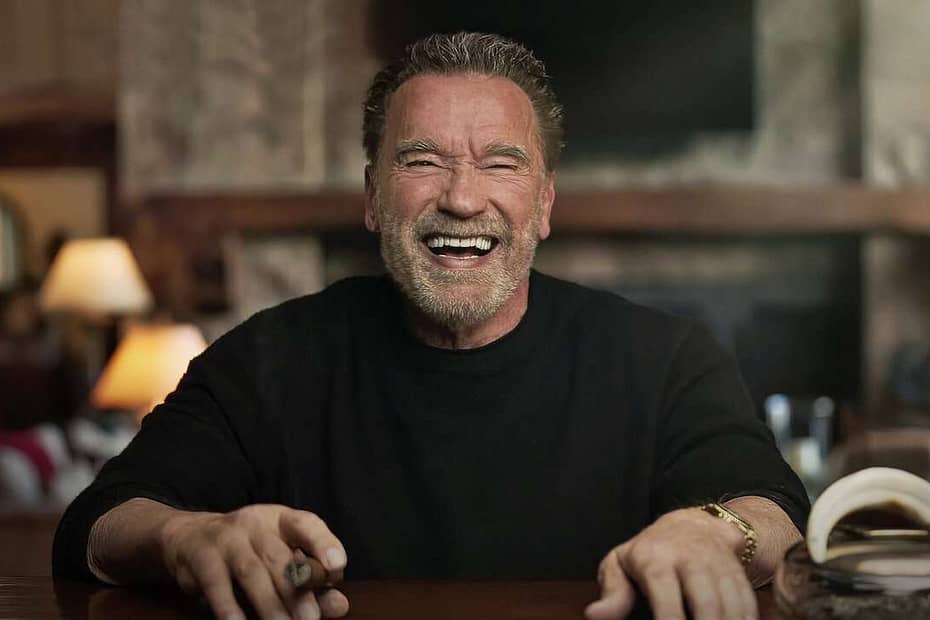

In ‘Athlete’, a grizzled, grey-bearded Arnold, diminished but looking good for his three quarters of a century, recounts dreamily how, walking around Graz with his brother Meinhardt after school, he saw poster outside a cinema for a Hercules movie starring Reg Park.

“I was kind of like in a trance. Who IS that?” I went in and I saw this body and I was so amazed at this body that I could not get it out of my mind. The testosterone was kicking in. Getting interested in girls was kicking in. Everything started happening.”

Everything started happening…

“Then I walked by this store full of American stuff. One of the things was muscle magazines from America. This guy Reg Park that I saw in the Hercules movie, he’s on the cover. Inside it has his training program – says he trains three times a day, ‘well I have do that’ I said to myself – ‘Oh my god! this is my idol!’ So he was kind of my blueprint.”

Young Arnold was looking for blueprints. And maps. He had already decided he didn’t belong in Austria and was looking for the way out. He told himself (in one of his favourite phrases in the doc) “there’s something off here”. Like the protagonist in a fairy tale – and he himself, as a tireless self-mythologiser, constantly compares his own life story to a fairy tale – he began to think that he had been born to the wrong family. Like Harry Potter, his real antecedents had to be more glamorous.

“The more I read about the outside world, the more I thought: ‘I don’t think I was brought up in the right place, there’s something off here’. I know this sounds crazy, but for a while I thought ‘Maybe my dad isn’t really my dad, maybe it’s an American soldier’”. [Austria was occupied by American soldiers in the post-war period.]

Given that his father Gustav was a stern disciplinarian local police chief (and ex-Nazi – though this isn’t mentioned), who was prone to drunken violence which terrorised him, his older brother Meinhardt, and his mother Aurelia, this wishful thinking isn’t so surprising. Even though it meant that his neat freak, floor-scrubbing, napkin folding, borderline OCD house-proud mutter would have been unfaithful to his father. (But according to one biographer, Gustav himself had an unfounded suspicion that Arnold was not his biological child.)

Arnold craved a more desirable paternity than the one he was sentenced to – and a more interesting destiny than he was supposed to have. And because Arnold was already in love with America and all things American, his escapist fantasy was full of stars and stripes: “I knew that bodybuilding was American, and that America was where I needed to be.”

His traditional Austrian parents didn’t approve of their son’s new-found passion for weight-training and looking in the mirror. His mother wanted him to learn a trade. His father wanted him to be a soccer player. Bodybuilding was weird. It was also – since Arnold hadn’t yet straightened it out, as he was to do in the 1970s and particularly the action-hero 1980s – more than a bit suspect.

“My father was negative because it was not the typical thing to do. The typical thing to do is to become a soccer player, or ski champion. ‘What the hell are you doing with this weightlifting? And you’re looking in the mirror while you’re doing it? What is all that about?’ He would say [sounds like to my ear – any German speakers?] ’Freuden! Freuden!’ – which kind of means ‘into yourself’. He says, ‘If you want to use your muscles, go chop wood.’”

His father wasn’t wrong. Bodybuilding is useless and narcissistic – gloriously so. Turning yourself into something to be ogled was a worryingly passive past-time for a red-blooded rural Austrian boy back then.

Arnold says, repeatedly, that his father’s generation were “broken men” – because of their experience of the war, and their defeat. His own father served as a military policeman on the Eastern Front, what the Nazis officially called the ‘War of Annihilation’, where the worst German atrocities occurred (and involved the Wehrmacht as a whole, not just SS units). The “broken men” theme is partly a way of explaining why his father like many others at the time was so harsh and unloving, but it is also a way of explaining how Arnold came to reject traditional Austrian masculinity – where you conform, do as you’re told, and work selflessly in a modest job to support your family.

And instead embraced the aestheticised, suspect Hollywood kind. Looking at yourself in the mirror. And dreaming BIG dreams. Bodybuilding was for Arnold a way of constructing a new identity and a new, more appealing, saleable, desirable, unbreakable kind of masculinity – in the post-war Austrian countryside. One that would, finally, succeed in conquering the world.

His mother had even more concerns about his bodybuilding obsession:

“And my mother got freaked out. ‘All his friends they have y’know, GIRLS above their bed. My son doesn’t have one girl up there. It’s only naked men, oiled up! Where did we go wrong??’”

We see the Arnie of today travel to his childhood home in idyllic Thal, Austria, which is now of course a museum (funded by Arnold himself) where he shows us his bedroom, with his worrying male beefcake photos pinned above his small single bed. This was where he hatched his plans of eye-catching world domination. Lying, somewhat awkwardly, on that bed the now elderly Most Famous Bodybuilder in the World tells us:

“I would be lying here like this and dreaming… and then looking up at those characters, then sitting up, I would see Reg Park, with his body, and then remembering the story of him growing up in Leeds, England, and the town was a factory town, like Graz, and the people worked hard. And I would say to myself, ‘And he made it out of that? Then there’s a chance for me also to make it out of here.’”

Arnold applies himself to the new, peculiar but exciting blue-collar trade of labouring on his own body – with Sisyphean dedication. He meets a group of male “weightlifters, bodybuilders, people with muscles” who regularly come to the lake at Thal to hang out.

“I all of sudden became part of this clique, like the young kid they were adopting. I think ever since then I celebrated this kind of camaraderie and because I admired it so much, I created that no matter where I went.”

His hard work in his bedroom and the gym quickly packs on mounds of muscle and whisks him away from Austria and to bodybuilding contests in Germany and London. Eventually, the fan meets his idol in London, in 1967, an encounter Arnie still describes in awed, quasi-romantic tones – and one which of course thousands of other new acolytes were to have later with him:

“Meeting Reg Park was one of those extraordinary moments. You see him in magazines. You see him in movies. And then all of a sudden there he is. He had just come from SA and wanted to work out. So, we worked out together. I remember he didn’t even take off his sweater. And it was just extraordinary to see Hercules that you saw in the movies and then to have a conversation and to have him be so nice.”

It seems a little ungenerous though of Mr Park not to take his sweater off. He did however become Arnold’s friend and mentor.

The next year Arnold won the Mr Universe title himself, becoming in effect his idol and completing the big dream that had kept him awake on his tiny bed in Thal:

‘At the age of 20 I made my vision become a reality. On that very same stage that Reg Park won it, and I got exactly the same trophy that he got. And exactly the way I envisioned it. All the people were screaming. I felt like, this was a fairytale. Everything falls into place.’

America finally notices its biggest fan, and Schwarzenegger is invited to California by the bodybuilding magnate and Mr Olympia creator Joe Weider – and the rest of the Amero-Teutonic fairytale (eventually) comes true. The Austrian Cinders becomes a Hollywood Prince.

In the doc he claims his famously confident, brash, bullying, cigar-chomping persona is mostly ‘schmah’ or ‘bullshit’. Or showbiz. He claims he has two personalities – the confident one we see, and the uber-critical one that is never satisfied with what it sees in the mirror, and it is the latter one that is responsible for his bodybuilding success. It was also bodybuilding, he says, that created the showbiz persona: “As a kid I was shy. And bodybuilding was a sport where you had to perform… this is how I became an entertainer.”

It’s difficult to know, though, with Arnold and Arnold where the schmah ends and he begins. Arnold is always ‘on’. Relentlessly.

Throughout the doc we see him “relaxing” in one of his sprawling, dimly-lit Californian homes, the fruit of his success (but alone, except for his many pets he dotes on), leafing through coffee-table books of glossy photos of himself, working out (alone again) in his gym, feeding and mucking out his livestock and quoting his father “Whatever you do Arnold, be useful!”. His marriage to the Kennedy scion Maria Shriver in 1986 produced four children but broke down in 2021 when it emerged that he had fathered a son with household employee Mildred Patricia Baena.

I doubt that Arnold is alone much, and he has a long-term 48-year-old female lover, but it appears he wishes to convey in the doc an image of penitence for his unfaithfulness – “I have caused enough pain for my family. I’m going to have to live with it the rest of my life” – and for the many historical accusations of sexual harassment/groping that emerged when he was running for office, for which he apologises here again, saying that there were “no excuses”, it was simply “wrong”.

He also goes out of his way to deny that he is a “self-made man” and cites all the people who helped him at various stages of his career. He offers a touching tribute to his lifelong close friendship with the diminutive but powerful and good-looking Italian bodybuilder Franco Columbu – “my favourite training partner” – whom he persuaded Joe Weider to bring to California to work out with him, was Best Man at his wedding, and godfather to his children, and who died in 2019, aged seventy-eight.

But it’s only when he expresses honest disappointment – well, disgust, actually – with his ageing body, that you know for certain he is completely schmah free: “I looked at myself in the mirror and thought ‘What the fuck?!’” (He has learned to adjust, albeit reluctantly, to the reality of his mortality – which is more than I have achieved.)

The distinction between what is and isn’t schmah is so difficult to draw because Schwarzenegger is schmah. Arnold Schmahzenegger. Without the schmah he disappears. For a while he seemed to be the charismatic but “emotionless, unstoppable German machine” that Joe Weider and the doc Pumping Iron sold him as being – and also, of course, Terminator. This was his most famous and popular iteration, which later ones all traded on. He famously claimed – and repeats the claim in the doc, that he didn’t attend his mother or his father’s funeral because grief would have distracted him from his training. In a sense, he was sold as a successful, sexy, showbiz version of the Teutonic masculine stereotype that broke his father and set the world ablaze.

But just as that iteration of Schwarzenegger was mostly marketing, the later, more touchy-feely Schwarzenegger is as well. There’s “something off here”. Becoming a family man, I’m sure, had a softening effect, but his political ambitions – to which his family life was inextricably connected – meant that he had to become more obviously ‘sensitive’, particularly to appeal to women voters.

This may be why he briefly accepted the ‘metrosexual’ moniker in the year that he ran for office: the media-marketing version didn’t mention self-love and was instead ‘a man in touch with his feminine side’. Despite or because of having used the phrase “girlie men” to attack political opponents in the past (and again in 2004, when the anti-metrosexual backlash was in full swing in the US). His winning political strategy when in office was also to position himself as a “centrist” and adopt touchy-feely “green” measures that showed he “cared”. A template that was to be adopted later by many other opportunist, narcissistic politicians, from Obama to Trudeau.

His older brother Meinhardt was the real touchy-feely Schwarzenegger. He died in a drunken car crash in 1971, aged just twenty-four. Arnold suggests his brother was “delicate” and that his father’s beatings and hyper-critical behaviour drove his brother into alcoholism.

“He was very artistic. Very smart. Read a lot, but I don’t think my brother ever was really happy… I think he started drinking because our upbringing was very tough.”

Arnold explains that his father’s “strange violence” was beneficial for him, making him “very strong” and “determined.” Reemphasizing that his brother “was more fragile,” and going on to invoke a famous phrase from Nineteenth Century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

“Nietzsche was right, ‘That that does not kill you will make you stronger.’ The very thing that made me who I am today was the very thing that destroyed him.”

I’m not sure that was quite what Nietzsche – who was himself very “delicate” – had in mind. But it’s telling that even the new, touchy-feely Arnold uses his brother’s sad death to emphasise his own monumental, global, gargantuan success.