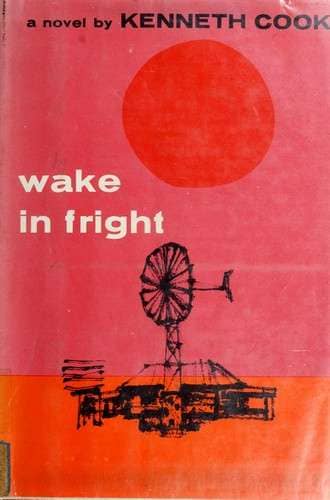

So, I got around to reading Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel Wake in Fright (recommended by S.J. Watson) which the film of the same name was based on, and which I wrote about here.

It is a remarkable, vivid, and wry piece of writing, still fresh after over half a century, and I thoroughly recommend it. The prose is sparse but powerful, sometimes poetic. The evocation of the unforgiving and unknowable landscape of the outback, particularly during the drunken night-time kangaroo hunt beneath the ‘the black, black, purple black sky which only the stars could penetrate’ is ‘transporting’:

The stars, the western stars, so many, so bright, so close, so clean, so clear; splitting the sky in remorseless frigidity; pure stars, unemotional stars; stars in command of the night and themselves; undemanding and unforgiving; excelling in their being and forming God’s incontrovertible argument against the charge of error in creating the west.

(p. 83).

Cook’s book, written when he was thirty-two, was based on his time working as a journalist in the mining town of Broken Hill, New South Wales, which he turns into the Western Australian town of ‘The Yabba’. Like Grant he was a Sydney man who found himself a long way from the sea. In over six decades since its publication, his first novel has never been out of print – and though the high regard of the film based on it may be part of the reason, it’s more likely because it is just a fine, timeless piece of writing. (Cook died in 1987, aged fifty-seven, the author of seventeen novels.)

The film adaptation is in many ways touchingly faithful, retaining much of the pristine dialogue and detail.

However, there are some differences. Some more important than others.

Cook’s John Grant is younger than Gary Bond’s (very well-preserved) thirty– probably early twenties. Just before his abortive tryst with Janette he remembers that he ‘had never had a woman before, and he knew that if he were more sober, he would have been startled by the thought’. Robyn, his Sydney girlfriend is someone he thinks about occasionally, but is not really a girlfriend – rather an aspiration. She is out of his league and barely aware he exists. For a while – before he gambles them all away – he thinks his winnings from the two-up club might impress her. The film’s device of showing a photo of her in his wallet that looks like a magazine clipping conveys all of this very well.

If anything, the mateship and friendliness of the Yabba men is even more pronounced on the page. The two big, broken-nosed miners (and ex professional boxers) Joe and Dick, for instance, who take John and Doc kangaroo hunting, are exceedingly kind to the young schoolteacher, buying him food and smokes as well as booze, and gifting him a rifle. (Though they are less kind to the kangaroos.)

In the film they are portrayed unsympathetically and menacingly, brutish even, to add tension and drama, and make a point about outback masculinity’s dark side, but on the page, they are, well, adorable. Everyone thinks they are brothers as they look so alike, but in fact they are not related. In fact, they are so alike that John keeps confusing them, every time he does, they correct him gently and good-humouredly. This is especially impressive since one of them is involved with Janette but overcomes his brief moment of jealousy over John’s brief moment with her.

Joe and Dick’s ’brotherly’ likeness, their inseparability, and their boxer past, inclined me to read too much into Joe’s reply to John’s question about how they ended up in The Yabba: ‘me and Dick drifted in here together and we stuck.’

Most significantly, Doc Tydon is a much smaller character – and person. Less sympathetic, less interesting. John meets him later in the book than the film, which expands his part considerably: allowing him to offer an eloquent critique of John’s pretensions and explanation of the Yabba ethos. I suppose that if you were going to go after Donald Pleasence, you’d have to have a decent part for him – and anyway you wouldn’t want to waste him.

In Cook’s text, once John leaves Doc’s shack in haste the Morning After, he never sees him again. There is no furious, raging return to his cabin with the rifle. Instead, once he lands back in The Yabba like a miserable boomerang, John ends up in a park, where he tries to kill himself simply out of despair. Recovering in hospital, he has an encounter with Janette (instead of Doc in the film) – one nearly as embarrassing as the first.

The film adaptation’s clever addition/extrapolation was to turn John and Doc’s non-relationship into a sort of twisted love affair – a symbolic sexual awakening that uptight John wanted but didn’t want. It remains kinda-sorta true to the novel, psychologically – by bringing out a homoerotic subtext. And giving us Gary Bond’s tan-lined bubble butt prostate on a bed.

The novel was adapted for film by Evan Jones, who wrote the screenplay for 1969’s Two Gentlemen Sharing (also directed by Ted Kotcheff), which is about, in a coded way, a white middle-class repressed homosexual relationship with his Oxford-educated young black Jamaican male flatmate.

As for that scene – the film version’s ‘climax’, if you don’t count the self-shooting scene – well, in the book it is if anything even more ambiguous than on the screen. And yet somehow not, at the same time. It could be sexual assault. It could be consensual. It is unclear – what is clear that something happens. Twice. And in a way that makes the significance of the book’s title clearer.

Then, Oh God! The light was bright and this could not be. Tydon. But the light went out. Then he went out. That was terrible. It should not have happened.

Nothing for a time.

Oh God! The light was bright and this could not be, again. It was all to do with being drunk because this could not, did not, happen to John Grant, schoolteacher and something. Tydon was a foul thing. But so was John Grant. Oh God, that light! But it was going out. And it went out. But what had happened before was terrible.

It should not have happened. It could not have happened. It had happened twice. And then nothing for a long time.

(p. 93)

I feel though that Jones, like me, zeroed on one particular passage – ‘It was all to do with being drunk because this could not, did not, happen to John Grant, schoolteacher and something… Oh god, that light!’ – as the key to understanding everything.

And with that, you’ll be glad to hear that I promise now to turn off that light, draw a sheet of modesty over the naked Australasian continent, and finally shut up about it and bloody ‘mateship’.