How Luhrmann’s ‘Elvis’ biopic undresses your mind

Twenty-two years ago, when this now heavily skid-marked millennium was still brand, spanking new, I went to see a restored, remastered version of the classic 1970 rockumentary Elvis: That’s The Way It Is, about Mr Presley’s return to live performance in Vegas. I swooned, screamed, and got a more than a little carried away, drinking in the King on the big screen, and penned a rather pretentious essay for the Independent about Elvis ‘the virile degenerate’:

Radiantly narcissistic, and dramatically unable to negotiate his Oedipus Complex, he is the prime idolatrous icon of a decadent, post-patriarchal age… he may not have invented virile degeneracy (Clift, Brando, and Dean, whom he imitated, have a prior claim), but he patented it. It may have been campy Liberace who was accused of being the ‘quivering distillation of mother-love’, but it was good ol’ boy Elvis-the-pelvis – and Liberace fan – who got away with it, and in fact made it cool.

Elvis, the beautiful boy who loved his mammy and almost forgot he had a daddy (as we did too: we always call him by his first name), the boy who desired to be desired so much he persuaded the whole world to eat him up, is the patron saint of the New Matriarchy.

Even today, twenty-three years after his death, as we stumble into a century he never actually swung his hips in, Elvis the rock star, pop star, stand-up comedian, and self-medicating Vegas showgirl, remains the acme of the mediated male, and of male desirability. Male love-me-tender passivity and vulnerability was endorsed, legitimised, and transmitted by The King –helpfully preparing men for the (prone) role that consumerism had in store for them.

Last week, forty-five years on from His death, I went to see Baz Luhrmann’s biopic Elvis and realised that my screed wasn’t pretentious enough. Luhrmann has also been carried away by Elvis. Ravished and covered in brooding, bourbon-soaked Southern kisses. Sometimes it even seems as if he has been carried away by Simpson carried away by Elvis.

Or as if I reviewed his film twenty-two years before it was released.

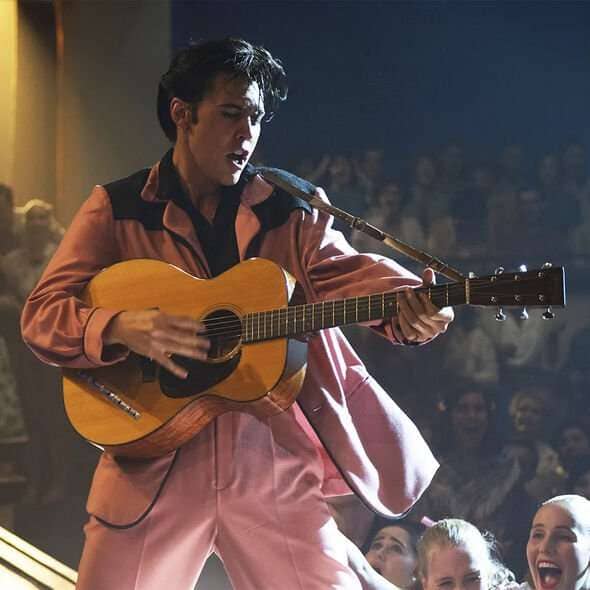

Elvis is gloriously, uproariously, intoxicating – and sentimentally if not historically accurate. For the first half. Which is mostly about Elvis-the-Pelvis’ then-scandalous and revolutionary male sex-object status: with oodles of unabashed zooming in on his shaking, big-trousered, high-waisted, 1950s crotch – which Baz presents from the POV of the screaming teen girls. Try as I might, I failed to discern any ‘commando’ activity – but the teen-girl gaze is clearly much more penetrating than mine.

His Faustian circus barker manager, Colonel Tom Parker (played with relish by Tom Hanks as the sulphurous antithesis of his usual Mr Nice-Slightly-Tedious) says he is looking for an act that gave the audience “feelings that they are not quite sure they should enjoy, but did, then I would have the greatest show on earth.”

Of course, Parker finds all that and more in the Memphis truck driver, Elvis Aaron Presley. The male stripper who remained fully clothed – while undressing the minds of his audience.

As should be clear from his other films, such as Moulin Rouge and Romeo & Juliet, Luhrmann doesn’t do subtle – hence his clear identification with Parker’s carny instincts. So, he shows us a nice, well-behaved, hoop-skirted teen girl in the audience of one of Elvis’ first hip-gyrating shows beginning to experience these unfamiliar, naughty feelings that she isn’t quite sure she should be enjoying, but really is. The scream that Elvis’ hips induce is presented as an initially hesitant – what IS this? – but finally, warmly-welcomed, first orgasm.

Baz, as I shall call him henceforth (using the legally-adopted nickname the then Mark Luhrmann’s school chums bestowed because of his Basil Brush haircut) also rams home Elvis’ unresolved Oedipal relationship with his mother, Gladys – who frets that Elvis’ success will “come between us” – and displays outright jealousy at the way girls throw themselves at her son. Of course, his success – and Parker – does come between them. Mightily.

When Elvis joins the Army at Parker’s bidding and is posted to Germany, she dies of alcoholism and a broken heart. Elvis for his part is shown destroyed by her death, clutching and sniffing the hems of her dresses as he lies sobbing on the floor of her walk-in closet – he was 23 at the time. (‘The quivering distillation of mother-love’.)

This is the moment Parker – officially diagnosed in the 1930s by the US Army as a psychopathic personality – is shown as becoming an unlikely and awkward mother figure for Elvis, explaining both his bizarre dependency on the old fraudster, and also his early death.

Elvis had been persuaded by Parker, supposedly now, due to his dubious past, in the pocket of the white supremacist Southern establishment, to do two years in the army as a way of silencing the growing moral and political backlash against his radical, degenerate, miscegnating hips – and turn him into an all-American boy fit for (white) family consumption. Elvis has to choose between two years in jail and two years in prison – after disobeying Parker’s strict instructions to keep his hips un-wiggled.

At this point it’s necessary, I’m afraid, to take a party-pooping reality check, in the form of Alanna Nash, author of the acclaimed 2003 book (which I’ve just ordered) The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley, recently interviewed by Variety about the accuracy of Baz’s Elvoid epic.

Overall, the extravagant liberties Baz takes are deemed fair – except to Parker: ‘In making him such an antagonist, they have robbed him of his many accomplishments with his client,’ concludes Nash. Who particularly rejects outright Baz’s portrayal of Parker suddenly trying to pressure Elvis to tone down the onstage sexiness:

No, no, not at all. Elvis took care of what Elvis did and Colonel took care of what Colonel did. He liked it that Elvis did what brought folks into the big tent. Listen, this guy was no fool! Parker loved it that Elvis was like a male striptease artist… like the bally girls on the carnivals. That sold tickets! The only time Parker got critical is when the shows began to falter with drugs or erratic behavior on stage. But that was in the ’70s.

Was there a late ’50s concert riot in which Elvis deliberately disobeyed Parker’s orders not to move around or wiggle on stage?

There were concert riots, most notably in Jacksonville, Fla., but not a concert for which Parker issued orders like that. No, all that stuff was rehearsed and rehearsed. Colonel knew what Elvis was doing and going to do. And again, he did not advise Elvis on any aspect of his performance. Headlines about how lascivious early Elvis was sold concert tickets. When Parker crony Gabe Tucker threw a magazine piece on the Colonel’s desk that insinuated that Elvis was gay, Parker didn’t say a word until his friend stopped sputtering. “Well,” Parker finally said, “Did they spell his name right?”

Elvis the lascivious, bally girl, striptease artist… virile degenerate. Aided and enthusiastically abetted by his low-morals manager.

Alas, Baz resorts more and more to the less and less convincing dramatic device of Parker trying to interfere in Elvis’ act, to tone him down, and to stop him being the true, authentic (and, yes, proto-woke) Elvis, as a way of holding the narrative and our contemporary attention together.

This often makes the second half of the movie as dull as the first half is brilliant. Which is particularly unfortunate as the movie is 2 hours and 39 minutes long.

The recreation of the famous be-leathered ‘68 Comeback’ TV special is as painstaking as it is pointless and seems to last longer than the fifty-minute original (which is anyway, all on YouTube), with some mostly fictional non-drama about Parker and the sponsor Singer sewing machines wanting Santa Claus and Christmas sweaters, while Elvis wanted protest.

No sooner is that out of the way, than Baz goes on to recreate, at length, Elvis: That’s The Way it Is his splendiferous, rhinestoned return to live performance (at the International Hotel, Las Vegas), including the rehearsal scenes with the Sweet Inspirations.

It isn’t altogether the Australian’s fault – popular music biopics today are contractually obliged to simulate what we have, in a visual culture, already seen many times. Just as pop music today simulates what we have already heard. And used to feel. I mean, Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) was essentially the 1985 Live Aid gig fetishistically imitated, with a bit of not entirely credible human-interest build-up: Wow! Look how amazingly close they got it to the video of the actual thing you can watch on YouTube!

Though perhaps, impersonation and simulation has been the whole point of pop culture since The King. And perhaps even the point of Elvis’ own career after he returned from military service. That’s why professional Elvis impersonators – before they died of old age years ago – always went for the Vegas era Presley.

I had to go and pee at the point where heavily indebted gambling addict Parker is selling Elvis’ immortal soul to Vegas hoods in a contract scribbled on a tablecloth. It’s both a sign of my age and the length of this movie that by the time the film ended I needed another pee.

Speaking of impersonators, the relatively unknown Austin Butler, who plays Elvis, is mesmerising in the young, pretty Elvis role, but lacks the brooding, slightly bruising quality of Original Elvis: he seems more Beverly Hills than Hillbilly. Sometimes, especially in sunglasses, he looks a bit Johnny Depp. But then, Johnny Depp was bound to look a bit Elvis.

I guess it’s in keeping with all that has happened since Elvis first swung his hips that Butler’s virile degenerate is less virile, more sweetly submissive. Even in Elvis’ late mutton-chop period we are spared the full muttonchop horror – and instead, offered vestigial, prosthetic muttonchops. (Just as in Bohemian Rhapsody, Rami Malek’s onstage Freddie Mercury is less butch – and has well-manicured armpits where Freddie’s were as bushy as Hampstead Heath).

Likewise, we are spared the unspeakable horror of the fat suit until the right at the end, when an ailing Elvis performs ‘Unchained Melody’ from the piano, shot in a grainy format partly designed to blend in with the archive footage, and partly to distance us and the film from his final, deadly, drugs-and-Parker-induced inauthenticity.

Bloated Elvis looks too much like… a Trump voter.

Commendably, Baz goes out of his way in the earlier part of his film to show Elvis’ natural love of black music and affinity with black performers. He even has shoeless boy Elvis peeping wide-eyed into a juke joint in Tupelo and then running into a black revivalist tent where he is shakingly possessed by the Holy Spirit, a scene as unlikely as it is powerfully symbolic.

Successful Elvis, under pressure to tone his act down, visits a dreamlike Beale Street, hangs out with BB King, watches R&B star Big Mama Thornton performing ‘Hound Dog’ (she was the first to record the Lieber & Stoller song), and Little Richard banging out ‘Tutti Frutti’ standing at the piana. (Which reminded me that a) Little Richard was the King AND Queen of rock and roll and b) made me wonder when is the big Little Richard biopic being made? And will it be Certificate 18 or just Pornhub?)

But, in the spirit of our times, Baz pushes it too far. Not just in the sense that Elvis’ many country music influences are erased, but the way that Baz’s Elvis, deeply affected by the assassination of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, and social injustice, is difficult to reconcile with the Elvis proudly photographed shaking hands in 1970 with the ‘Law & Order’ President Richard Nixon – after a meeting where he secretly offered his services in support of Nixon’s anti-drug, anti-hippy, anti-radical drive, and asked for a Narcotics Bureau badge. Oh, and he turned up wearing one of his thirty-seven hand-guns – a Colt 45. (A meeting, you won’t be surprised to hear, that doesn’t make it into Baz’s film – but was turned into one in 2016, with Kevin Spacey as Nixon.)

On the way out of my matinee viewing of Elvis – over two and a half hours older – stumbling blinking into the July sunshine, a turbo-charged mobility scooter driven on the pavement by a male pensioner nearly knocked me over. The superannuated tearaway was blaring out ‘Tutti Frutti’ on a boom box tied to the handlebars. As he zoomed past, he gave me a snaggle-toothed grin, and a thumbs up. So, I forgave him everything.

Rock and roll will surely live forever. But I have seen the Ghost of Christmas Future.