Mark Simpson looks at the British ritual of stripping off on the hallowed turf

(Independent on Sunday, July 1996)

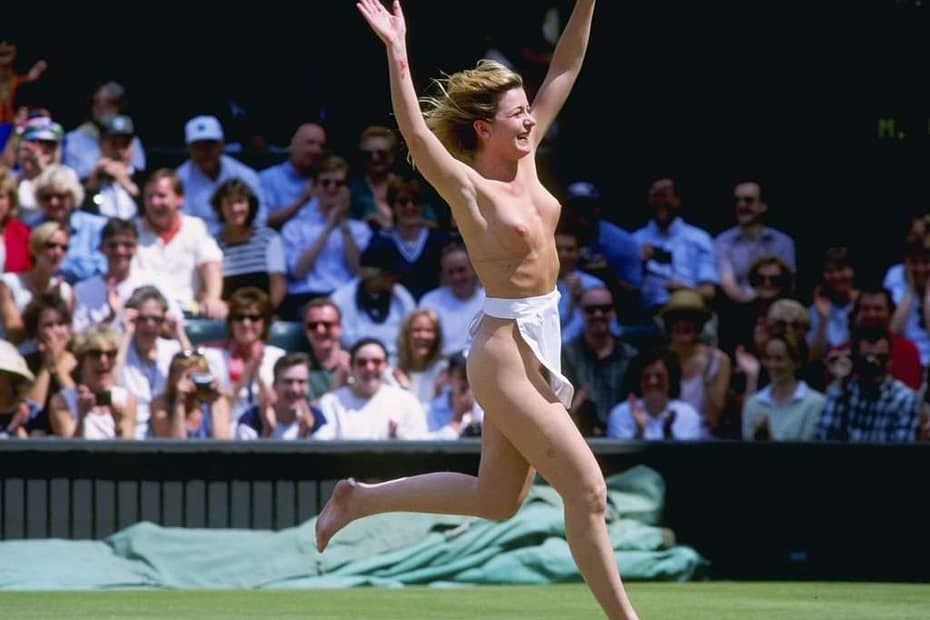

Melissa Johnson’s bra-less gallop across Wimbledon’s Centre Court this week in a skimpy pinny and lovely smile proved to be a moving experience in more ways than one. A deluge of press articles followed which waxed lyrical and nostalgic about a lost ‘golden age’ of public nudity.

‘Streaking has been in decline ever since it peaked in the seventies,’ lamented Barbara Amiel in the Daily Telegraph. ‘This decline has not been of benefit to our civilisation and we must all hope that Miss Johnson has given it a new lease of life… This is nudity pure and untarnished.’

You know that seventies revivalism has peaked when the Daily Telegraph harks back to the decade of Labour Governments, strikes and streakers. Of course, that The Thunderer can now afford to look forward to a revival of streaking merely illustrates how defunct streaking is, and how nudity nowadays is anything but ‘pure and untarnished’.

Streaking had its origins in women’s protest against puritanical ‘protection’. Female students on American campuses in the sixties, disgruntled at the way their bodies were policed – they were locked up in the evening ‘for their own safety’ – took to running naked across the campus to draw attention to their predicament.

Hence public nudity and streaking were from the beginning bound up with the idea of personal and sexual ‘liberation’ that the sixties came to represent. By the seventies streaking had become a way for the younger American generation to signal their contempt for the puritanical older generation that wanted to use their bodies to make war with, not love.

It wasn’t, however, until the famous invasion of the pitch at Twickenham in 1974 by a naked but bearded Mike O’Brien, his modestly famously protected by a strategically placed bobby’s helmet, that streaking really arrived in Britain. That it was presented in jokey terms was entirely to be expected. In Britain in the Seventies the body was less a battlefield than a comedy. This was, after all, the decade of Carry On films and Are You Being Served? The ‘permissiveness’ of the sixties allowed the British to acknowledge that they had bodies, if only to laugh at them.

But O’Brien was making a protest – a protest against being British. Just before he decided to streak, he had been discussing the streaking phenomenon in America with his friends and they had decided that it could never happen in ‘stuffy old Britain’. Unwittingly, in vaulting starkers over those wickets, O’Brien started a trend for streaking in the long hot summers of ’75 and ’76 which was to make streaking as British as cricket itself.

This was largely down to the British attitude to heat. Every year we Brits like to pretend to be amazed that the thermometer can rise above 70 degrees. Heat is supposed to be un-British, associated with Continentals and colonials. But this doesn’t mean that we don’t like heat – we love making a British fuss about it.

When the streaker, on some ‘gloriously’ hot sunny day, throws off his or her clothes (along with history, tradition, custom, class) and runs naked across such national institutions as Lords, Twickenham, and Wimbledon, they do so to cheers and tabloid headlines of ‘PHEW! WOT A SCORCHER!’ The peculiar nature of Britishness is that it is most generally affirmed in a communal statement of how much fun it is not to be British – for a while.

This is why the picture of a naked O’Brien at Twickenham surrounded by buttoned up policeman came to represent the ultimate image to the British both of a streaker and of Britishness. (O’Brien himself decided he needed a permanent holiday from being British – he now lives in Australia).

By the eighties, quaint British attitudes towards the body and nudity had been changed forever by the American-dominated image business and the world-wide marketplace. The protest of the seventies had turned into contest, liberation into domination. The body became an instrument for getting ahead, a weapon in the individualist war of all against all. Arnie the body-builder android in The Terminator, running around Los Angeles stripped of his clothes, and finally, his flesh, was the eighties zeitgeist streaker – his nakedness just revealed his steely, ruthless, be-pistoned determination.

Taking off your clothes in public, even in Britain, was now no longer about being nude but about being noticed. Erica Roe’s streak at Twickenham in 1982 is perhaps the last streak anyone can put a name to, precisely because it marked the end of streaking. There can be nothing ‘spontaneous’ about public nudity in a mediatised world where everything is an image to be bought and sold. Streaking becomes marketing. Roe landed a modelling contract and now regrets the fact that she didn’t have a publicist at the time to maximise her ‘exposure’ (as she launches a line of supermarket vegetables named after her).

In the nineties we are bombarded continually by ‘exposures’ and ‘revelations’. The ‘naked truth’ is always being presented to us; authority, history, sexuality are continually being disrobed and paraded. Ironically, the result of all this is that the one thing that can’t be ‘revealed’ any more is your own body. Stripping loses its meaning when it is surrounded by a culture where everything is always and already stripped bare; showing an ankle only has a charge when the culture insists on draping table legs with heavy velvet. When a Newcastle vicar recently invited people to streak in his church because they ‘cheered people up’ he effectively performed the last rites on nudity.

As the nostalgia provoked by Johnson’s Centre Court sprint shows, streaking nowadays is just an ironic re-enactment of a retro Athena poster moment. It has become another form of dressing up.