Mark Simpson totally relates to the author’s 1970s childhood war-fetish, but has to draw the line at Ernest Hemingway.

(Independent on Sunday, 31 March 2002)

Robert Twigger is a man who wins awards. The jacket of Being a Man… In The Lousy Modern World boasts of the Newdigate Prize for poetry, the Somerset Maugham Award and the William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award. Perhaps this because Twigger is very talented, or perhaps it’s just because Twigger is the kind of man who wins awards.

Whatever the answer, despite ringing testimonials on the same jacket from those well-known gatekeepers of masculinity Will Self (‘a tour de force’) and Tony Parsons (‘I urge you to read everything that carries his name’) the one prize which Twigger’s been aiming for all his life – manhood – still eludes him.

Or as Leighton Bailey, Michael Horden’s fabulously starchy boss in the 1956 Rank film The Spanish Gardener says when firing him, ‘It’s as a man you’ve failed’. (As proof, Horden’s son has deserted him for his ‘Spanish’ gardener, Dirk Bogarde – yes Dirk Bogarde. In fake tan.). Of course, nowadays most men are ‘failures’ – but being manly is not now a very smart career move and most men under forty don’t seem to care whether they’ve failed as men or not, just so long as they win in the soft, sybaritic consumerist marketplace.

Mr Twigger however, does. Very much. Which is nice, but the real question is: should we care about Twigger?

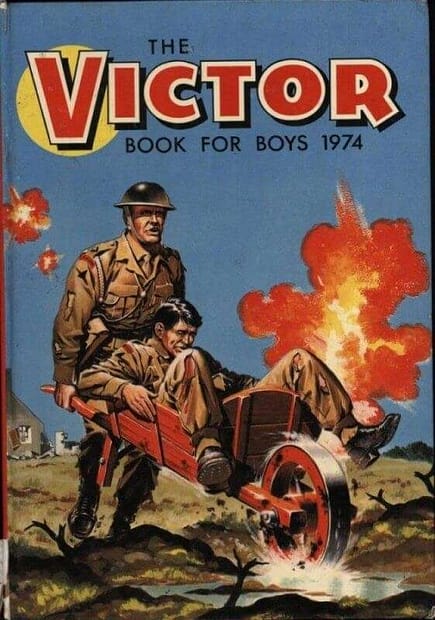

Certainly Twigger’s evocatively recounted 1970s lower middle-class childhood is entirely familiar to me and probably millions of others: that odd emphasis on service and sacrifice, stoicism and stiffened upper lips, forever preparing to fight a war that ended thirty years previously. I too was an avid fan of The Colditz Story, The Guns of Navarone, Dambusters, Hotspur, Commando Comics, Victor, Dad’s Army and playing war in abandoned pillboxes. ‘Never mind the seventies,’ Twigger writes, ‘flower power, flared jeans and platform soled shoes; for me and my friends it was all war, war, war.’

Life forever presented itself as a test that might prove you wanting: ‘I never saw a river without imagining someone was drowning in it and waiting to be rescued, a railway track without working out how to save someone who had fallen in front of a moving train…’ Of course, it was a shining, virtuous childhood which laughably failed to prepare Twigger – or me – for the ‘lousy modern world’. Both of us would have been much better off with the platform shoes and flares the street-smart boys on The Estate wore.

If he’d lived in my village, Twigger and I would probably have been blood brothers for a few summers, covering the countryside with slit trenches and promises of eternal comradeship. But I suspect we would have drifted apart eventually, round about the time that I realised he didn’t have much of a sense of humour. Or maybe when he realised that I had a bit of an over developed one.

‘Being a Man’, we’re told, contrasts ‘twenty-four hours of “normality” in Robert Twigger’s suburban existence with half a lifetime of (mis) adventurous living’. In other words, bragging reminisces and whimsy about masculinity woven around a narrative of holding a barbecue and taking his wife to the hospital to have their first child.

Now, I don’t mind a bit of masculine bravado, but the ‘nasty scrapes’ the author has managed to get himself into, how if it hadn’t been for the adrenaline rush he wouldn’t have been able to haul himself back into the boat/onto that mountain ledge/confront that bull in Pamplona (yes, he really did go bullfighting) are, alas, mostly quite tedious. Several times Twigger mentions that his father was down the pub when he was born – but despite the fact that Twigger actually witnesses his son’s birth, with ‘Being a Man’ he somehow manages to be down the pub with the reader of his book, boring them to death with his tales of derring-do.

Twigger’s failure is a failure of self-consciousness, twice over. His masculinity is a failure because he’s always looking for the secret, the code,the instructions (hence a fascination with martial arts); but in a self-reflexive world this is to be forgiven. However his writing here fails because it’s not self-conscious enough; he doesn’t seem to realise how comically self-defeating that literal-mindedness is, or be able to diagnose his own malady, let alone anyone else’s. This is not forgivable, even without the constant invocation of that American granddaddy of twats Hemingway (and the‘lousy’ use of Americanisms throughout the book).

Twigger’s boyish Army obsession continued until he was sixteen; when he realised that the only people who wanted to join the army were either ‘misfits, gay… or teetering on the edge of a nervous breakdown.’ Yes, right, OK, but Robert I still don’t know why didn’t you join….

When Twigger finds himself in Mothercare he finds a part of his brain screaming that ‘BUYING NAPPIES IS STRICTLY FOR FAGS!’, an interesting response but one that is not analysed or even commented on. In a particularly risible passage he discusses at great length the story about Papa Doc’s encounter with F. Scott Fitzgerald in which Scotty complained that his dick was too small: Hemingway asked to see it and authoritatively pronounced it ‘normal sized’.

Twigger then advances an agonisingly torturous and entirely unnecessary argument that Hemingway worried about the size of his penis. Is Twigger the last person on Earth to have ‘twigged’ this? What’s clear is that Twigger has worried about the size of his penis – which is nothing to be ashamed of, especially in a book about masculinity – but he doesn’t tell us about it, instead he literally tries to put it in Papa Doc’s mouth. Not a pretty sight.

Speaking of which, in the gay world, afflicted as it is by far too much self-consciousness, there’s a term called ‘straight acting’. It’s supposed to denote ‘non-effeminate’ but unfortunately, unless the practitioner has a sense of humour, it too often merely denotes ‘a pain’. Alas, it would appear that this condition is not to be sexuality-specific. I have another award for the award-winning Mr Twigger: The Ernest Hemingway Award for Straight Acting Heterosexuality.

As Twigger writes himself: ‘What follows may be bollocks, so be warned.’ A commendable and very necessary warning.

Shame it doesn’t appear until page 121.