The ‘crisis of masculinity’ is really a form of male emancipation argues Mark Simpson

(First appeared in Sweden’s SvD newspaper, 17/06/2017; published here in English with permission)

Back in the late 20th Century, when I first began writing about masculinity – which seems an epoch away now – everyone knew what masculinity was. Or rather, what is wasn’t. And what masculinity wasn’t was very, very important. As a man, your balls depended on it.

Masculinity wasn’t sensual or sensitive. It wasn’t good with colours. It wasn’t talkative, except about football. It wasn’t passive. It wasn’t nurturing. It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t feminine. And it certainly wasn’t gay. Masculinity was uniformity – difference was deviance.

Yes, I’m grossly stereotyping here. But that’s exactly what cultural expectations did to men.

And yes, masculinity could also be stoic, altruistic and heroic – but these ‘positive’ masculine qualities, which of course we’re all terribly nostalgic about in this selfie-obsessed century, were also based on repression. Being a man was much more about ‘no’ than ‘yes’. If you said ‘yes’ too much you might as well be a woman – or gay.

Because everyone knew what masculinity was – or wasn’t – hardly anyone talked about it. Apart from feminists and gays. Anyone who used the ‘m’ word was a bit suspect, frankly. And I was very suspect indeed – especially when I insisted that the future was metrosexual. Masculinity was supposed to be taciturn and self-evident not self-conscious and moisturised. No wonder I was laughed at.

More than a decade and a half into the nicely-hydrated 21st Century, everyone is now talking about masculinity. There is also a great deal of media chatter, from both ends of the political spectrum, about a so-called ‘crisis of masculinity’ – and a tendency to suggest that today’s generation of men are in a bad way compared to their forefathers, and also compared to women.

I couldn’t disagree more. There has never been a better, freer time to be a man. Which is precisely why we’re actually able to talk about the ‘m’ word. Yes many men, particularly older men who grew up with a model of masculinity that isn’t working for them any more, do of course face new and real problems in our rapidly-changing world – and sexism is, as the word suggests, a two-way street. But today’s ‘crisis of masculinity’ is basically the crisis of a man whose cell door has been left ajar.

In a sense, masculinity has always been ‘in crisis’ – a degree of hysteria was in-built because it was about living up to impossible, nostalgic expectations. Even the Ancient Greeks were worrying that men weren’t what they used to be: Homer’s Iliad is essentially a love letter to the ‘real’ men of the Bronze Age – heroes that made Iron Age men look like proper sissies.

Today’s men are probably less in ‘crisis’ than they have ever been before because those impossible, ‘heroic’ expectations have largely fallen away, and along with them the masculine prohibitions. Even that reactionary trend for lists of ‘man code’ ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ is just another sign of this. If you have to spell them out in a prissy list then they’re really not working any more. They were supposed to be completely internalised.

Everyone is asking ‘how to be a man’ now because no one really knows the answer. Which is actually great news! Rather than something to worry about. It means that everything is up for grabs. Men today are beginning to aspire to what women have been encouraged to aspire to for some time now – everything.

Repression, once the bedrock of masculinity, is definitely out of fashion. After all, we live in a hypervisual, social me-dia world where expression is the lingua franca. If you don’t express yourself you don’t exist. Today’s young men are mostly much more interested in being and feeling and sharing than in denying and hiding. They have tasted the forbidden fruits of sensuality, sensitivity, taking an interest in their own kids (if they have them), being good with colours, or having a prostate massage, and want more, please.

In fact, for the younger generation most of these masculine ‘transgressions’ are now pretty much taken for granted. Metrosexuality – the ‘soft’ and ‘passive’ male desire to be desired – is the new normal. Products, practises and pleasures previously associated – on pain of ridicule – only with gays and women have been more or less fully-appropriated by guys.

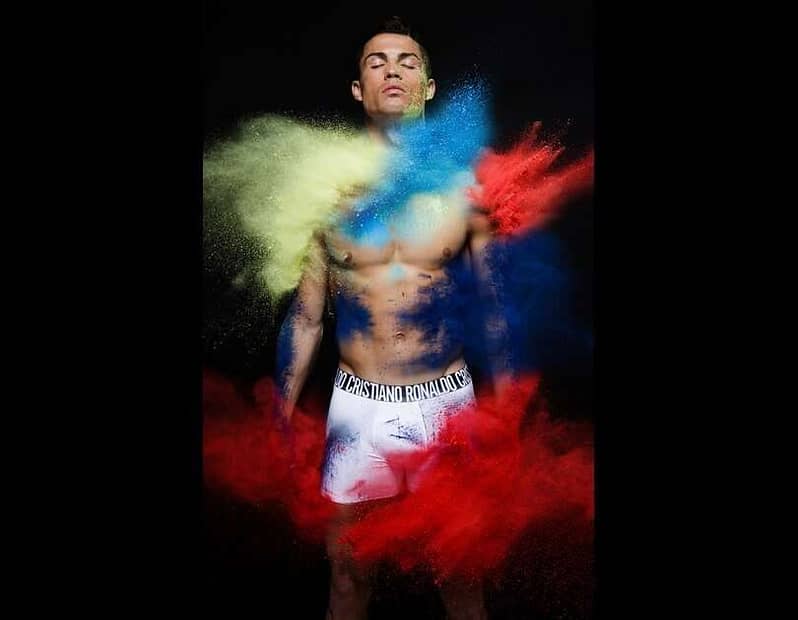

The most obvious, flagrant example of this is what has happened to the male body. No longer simply an instrumental thing labouring in darkness, extracting coal, building ships, fighting wars, making babies and putting out the rubbish, it has been radically and sensually redesigned to give and especially receive pleasure. It has become a pumped and waxed brightly-lit bouncy castle for the eyes.

Today’s eagerly self-objectifying young spornosexuals – or second generation, body-centred metrosexuals – toil in the gym in their own time to turn their bodies into hot commodities that are ‘shared’ and ‘liked’ in the online marketplace of Instagram and Facebook. Which is certainly needy, but also very generous of them. Young straight(ish) men today have taken the gay love of the male body and buffed it up – and want to share that love.

There is no crisis of masculinity – but rather, a long overdue crisis of the heterosexual division of labour, looking, and loving with which the Victorians stamped most of the 20th Century. Freed from the imperative to be ‘manly’ and (re)‘productive’, men have blossomed into something beautiful. A word that until very recently was absolutely not supposed to describe men.

Obviously the rise of feminism and gay rights have helped changed men’s attitudes. But perhaps the boot is on the other foot. Men in general are much less hard on gay men and on women now because they are no longer so hard on themselves. In a sense, women and particularly gays existed to project all men’s own forbidden ‘weaknesses’ into.

Nowadays, having been allowed to discover the pleasure they can bring, men want those ‘weaknesses’ back, thanks very much.