By Mark Simpson

IN THE EARLY YEARS of the 1980s, stretch jeans were all the rage. Stretch jeans and The Human League’s Dare. Both were revolutionary but practical and, when wrapped around youth, snugly-smugly invincible.

I was sweet sixteen when Dare was released in 1981 and it confirmed all the psychoses of teenagerdom. We thought the future belonged to us and our arrogant thighs, with our denim-spandex mix and new-fangled dance-orientated synth-pop. We thought we were so fucking clever. So fucking fuckable. And we were so fucking right, even if our future didn’t turn out to be quite so cool and snug and fun as we thought it would be.

Dare had the effrontery to stretch the sparse, avant-garde, electronic dreams of the early, pre-1980 split, art skool Human League around pop music, disco and everyday desire. It was a perfect, thrilling, highly sexy fit. There’s a simple, timeless test of whether pop music is any good or not: can it be played really loudly at a fairground while you’re being spun around by a tattooed lad on the Waltzers?

To this day, whenever I hear the opening bars of ‘Love Action (I Believe in Love)’, the bit which sounds like flying saucers talking to one another before the hip-wiggling bass line kicks in, the hairs still obediently rise on the back of my neck and I’m all giddy and spotty and about to spew up my Merrydown again.

Dare is one of the greatest pop albums ever made, and quite possibly the greatest UK dance album. It changed what pop music could be. It changed what the world was going to be. This thrice-platinum album was wildly successful and influential, cool and high street, arty and commercial, on a scale that has never really been repeated and can never be, now that pop music is essentially a spent force.

And this cultural colossus (with a little help from Virgin Records) stepped out of the post-industrial wreckage of ‘Steel City’ aka Sheffield. Not London, not Manchester, but the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire. Tyke pop.

There’s a simple, timeless test of whether pop music is any good or not: can it be played really loudly while you’re being spun around by a tattooed lad on the Waltzers?

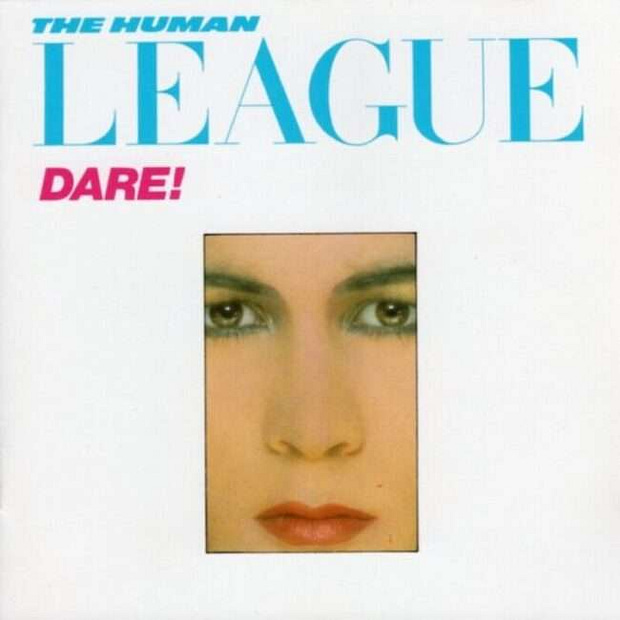

The Vogue-styled album gate fold cover, with The League’s devastatingly pretty and provocatively made-up lead singer (and now unchallenged creative director/dictator) Phil Oakey as front-cover girl – with Susan Ann Sulley and Joanne Catherall, the pretty schoolgirl dancers/backing vocalists famously recruited by Oakey in a Sheffield nightclub called Crazy Daisy’s, barely managing to compete on the inside. (Philip Adrian Wright, the only surviving non-Oakey member of the pre-split Human League, was not given the Vogue treatment.) It was a work of pop art that Factory Records, just over the Pennines, might have envied – if they weren’t so post-punk puritanical.

Listening today, over thirty years on, almost nothing has aged about this album, recorded at the very apogee of synthpop and its analogue daydreams of a digital world – this, after all, is what ‘synthpop’ was before digital technology actually, finally arrived years later, and ruined everything. Those Korgs and Rolands were analogue. It is much, much easier to make synthpop music now, and almost everyone does. But none of it has any heart.

The first track, ‘The Things That Dreams Are Made Of’, an anthemic invocation of desire, exhorts the listener to ‘do all the things you ever dared’. The stirring football chant chorus:

These are the things! These are the things! The things that dreams are made of!

is undercut by the almost banal modesty of the detail of those dreams:

New York, ice cream, TV, travel, good times.

But that’s the intoxicating drama of Dare: a utopian soundtrack with a down-to-earth, suburban ‘good time’ vibe:

Everybody needs love and affection. Everybody needs two or three friends.

By the austere, highly political post-punk standards of a Thatcher-ravaged, deeply recessed 1981, Dare demanded the impossible.

The new, purged Human League’s first offspring was very much Oakey’s baby. It really was ‘Phil talking’, having rid himself of dissenting voices of Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh, who went on to form Heaven 17 (and take on that fascist groove thang). Phil’s inimitable baritone suffuses the album – a voice as distinctive as the sound and the look. A voice so distinctive, in fact, that like many from that era, it’s impossible to imagine it succeeding today. Except perhaps as a novelty act to be voted off before the semi-finals.

Martin Rushent, the synth-pop producer brought in to make good the loss of the technical skills of Ware and Marsh, should be credited as a fifth band member on Dare. His virtuoso deployment of synths and sequencers effectively adds another lead vocal to the tracks, while the introductory bars are micro-overtures that instantly announce the irresistible genius of each song. Is there an album anywhere that has better, hookier, more outrageously sashaying intros? ‘The Things That Dreams Are Made Of’, ‘The Sound of the Crowd’, ‘Open Your Heart’, ‘Love Action’, and the Sheffield nitespot operetta of ‘Don’t You Want Me Baby?’ – da da da-da dum da da da DUM!

You know exactly what’s coming and you can’t wait. Much like love itself.

The final track ‘Don’t You Want Me Baby’ became of course the Human League’s best-selling single and 1981’s Xmas Number One, selling over two million copies worldwide. It is also the most perfect pop song ever made, running the sublime gamut from epic to trashy and back again, with a sing-along chorus that is the purest distillation of all pop lyrics ever:

Don’t you want me baby? Don’t you want me, OHHHHH!

After that there really is nothing more to be said on the subject.

‘DYWM’ brings perfect ‘closure’ to Dare’s theme of pursuing dreams. Oakey plays a Svengali figure spurned by his creation, voiced pitch-perfect by Susan Anne Sully, and threatens:

Don’t forget it’s me who put you where you are now And I can put you back down too

She’s ‘dared’ – and doesn’t need him anymore. But the biggest Dare of all was Oakey’s. Everyone thought boffins and band founders Ware and Marsh were the brains of the outfit and hence Oakey would fall flat on his pretty-boy face after the 1980 split. Phil was working not as a cocktail waitress but as a hospital porter when Ware found him in 1978 and turned him into someone new.

But his worst turned out to be better than their best.

(Originally appeared on Culture Kicks, June 5 2013)