Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Cash Nexus: Money and Power in the Modern World‘ reviewed by Mark Simpson

(Originally appeared in the Independent on Sunday, 2001)

How sexy and right wing is the historian Niall Ferguson? It’s no idle question, since sexy right-wing historians can gain fame and fortune, that’s to say – money and power – in the modern world.

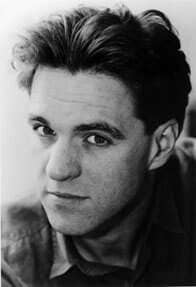

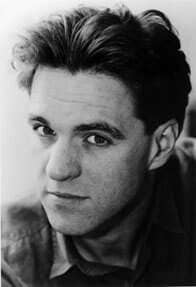

The first name is a good start, reading as it does like a Celtic battle-cry. And he’s young. In fact, the half-profile picture of him on the inside jacket is fetching and flirtatious, in a rugby-playing New Romantic kind of way (dark, round, inviting eyes, but the flattened nose hints at brutality). The title of course is certainly ‘sexus’, while the subtitle, ‘Money and Power in the Modern World’ practically promises pornography. Just in case we miss this, the jacket blurb tells us that money is ‘the sinews of war’ and that the cash nexus ‘is the crucial point where money and power meet.’ (And yes, there are illustrations).

Unfortunately, The Cash Nexus is a terrible tease, and, for the most part, Ferguson turns out to be not nearly sexy and right wing enough for my cash. Alas, you see, he’s too busy being an historian. The ‘crucial point where money and power meet’ turns out to be a sober, painstaking, somewhat frigid history of taxation, national debt and the bond markets. Diligently researched, full of tables and graphs (many of the latter impressively unreadable), balanced and dispassionate, The Cash Nexus is exactly as sexy a book as you would expect to find emerging out of a year spent in the bowels of the Bank of England Library; the vital statistics Fergie’s interested in are unlikely to raise many pulses outside academe and accountancy internet Newsgroups.

This is not to say that Ferguson’s findings, particularly about the crucial role of financial institutions in spreading the huge costs of war (and the crucial role of war in developing financial institutions), aren’t in themselves interesting or important, it’s just that for much of the book they haven’t been martialed into a cohesive argument, or even into particularly muscular prose. This is one of the strengths of the book as a resource, but not as something you might actually want to read. I found myself begging Fergie to say something outrageous, to stick his rhetorical jaw out and lash me with a reactionary soundbite, to wave a whopping great weltanschauung in my face, choke me on the audacity and arrogance of a sweeping generalisation but, except for the occasional mean-spirited kicking of Marxist historians like Eric Hobsbawn and pinko sociologists like Anthony Giddens, it mostly didn’t happen.

Like many British right-wing historians, Ferguson is too busy being besotted with institutions to be really provocative. For Ferguson it is the superiority of British financial, fiscal, and parliamentary institutions – and above all property rights – which guaranteed British hegemony in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century, despite the fact that France wielded a much larger population and paper resources than Britain. Britannia, helped by Mr Rothschild, was better able to make efficient use of her resources and revenues and maintain a much higher level of war debt and ultimately grind the Froggies down (producing over three times as many ships). He may well be right, but it’s really too depressing to think that France was defeated not by Hornblower and the jolly jack tar, but by tax collectors and rentiers.

It isn’t until almost at the very end of the book, after a Long (and dusty) March through the Institutions, that Mr Ferguson finally takes off his bifocals, rolls up his shirtsleeves and begins to get seriously sexy and right wing. Taking on the commonly held notion of ‘overstretch’ and the crude economic determinism behind it, in which Empires are thought to fatally weaken themselves and hasten their downfall by excessive military spending to meet their over-extended commitments, he argues – tightly – that in fact understretch is the real problem. Britain, for example, could, he claims, have afforded to spend more on defending the Empire before 1914 and 1939, and he manfully quashes the slack, pinko consensus that it was inevitably doomed, that we couldn’t have afforded to maintain a land army large enough to deter the Bosch.

By the same token he argues strongly against the idea that the Imperial US is now suffering from overstretch. He shows that Reagan’s military build-up of the 1980s was not as costly for the US as is generally thought and that in fact since the late Eighties the proportionate level of US defence spending has been historically low. On the other hand, the USSR probably did suffer from ‘overstretch’, but mostly because economic stagnation, poor institutional development and a failure to access the bond market meant that the arms race cut into production and investment and thence into production again.

Ironically, Emperor George Bush II has promised to increase military spending but also to finally abandon the US’s post-war role as ‘international policeman’ – the missile shield/security blanket being the symbol of this withdrawal. Ferguson castigates this attitude and argues that the problem with the US is that it isn’t imperial enough. It has churlishly refused to take on the responsibilities that Empire requires, in contrast to stalwart Britain in the Nineteenth Century. The US, for example, should lead an expedition against Saddam Hussein to depose him an install a democratic regime loyal to the West.

It’s an admirably explicit, manfully robust argument which Ferguson manages to present as if it is the product of the same cool accounting and dry, dusty logic that has featured in much of the rest of the book. However, I can’t help but feel that this talk of ‘understretch’ and this apparent appetite for war actually emanates from a more emotional, more passionate place – an almost Roman, visceral horror at the lax and louche enervations of decadence.

Comments are closed.