The mythology, the dogtag dogma, the cult of masculinity and most of all the haircut, set US Marines apart. Mark Simpson on a memoir of the First Gulf War.

(Independent on Sunday 23/03/2003)

It may seem odd that the United States Marine Corps, the elite fourth branch of the US Armed Services, larger and better equipped than the whole British Army, heroic victors of Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal, spearhead of the last and current Gulf War, should be best known for, and most proud of, its hairdo. But then, the USMC is a peculiar institution. Magnificent, but very peculiar.

“Jarhead”, the moniker US marines give one another, derives from the distinctive “high and tight” buzzcut that Marine Corps barbers dispense, leaving perhaps a quarter of an inch of personality on top and plenty of naked, anonymous scalp on the sides. Like circumcision and the Hebrews, the jarhead barnet has historically set US marines apart, marking them as the chosen and the damned: monkish warriors. Or as one of the Corps’ mottos has it: “The Few, The Proud”.

Image is important for US marines, perhaps because of the burden of symbolism – for many, the USMC is America. Or perhaps more particularly because the USMC is John Wayne. Jarheads, or rather, actors in high-and-tight haircuts, are invariably the stars of Hollywood war movies; the other services just don’t have the glamour and the grit of the devildogs. As a result, the mythology, the rituals and the dogtag dogma of the Marine Corps cult of masculinity – boot camp, the DI, sounding-off, cussing and hazing, tearful graduation, test-of-manhood deployment, and that haircut – are probably more familiar to British boys than, say, those of the Royal Marines.

The relationship of real jarheads to their actress impersonators is confusingly close. When 20-year-old Lance Corporal Anthony Swofford and his buddies in a scout/sniper platoon get the order to prepare to ship out to Saudi Arabia in 1990 in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, they spend three days drinking beer and watching war movies. Ironically, their favourite films, such as Platoon, Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket are ostensibly “anti-war” liberal pleas to “end this madness”, but for fighting men they only serve to get them hot: “Filmic images of death and carnage are pornography for the military man,” explains Swofford, “with film you are stroking his cock, tickling his balls with the pink feather of history, getting him ready for his First Fuck.” Take note, Oliver Stone, you pink feather dick-tickler: “As a young man raised on the films of the Vietnam War, I want ammunition and alcohol and dope, I want to screw some whores and kill some Iraqi motherfuckers.”

In fact, Swofford’s ”Jarhead: A Marine’s chronicle of the Gulf War’’ is an avowedly “anti-war” memoir, powerfully written (pink feathers aside) and well-crafted, by someone who was clearly embittered, not to say damaged, by his experience of the USMC and his participation in the First Gulf War. Nevertheless, it isn’t clear whether Swofford, for all his reflectiveness, and of course his authenticity, is much more successful in demystifying war in general or the Corps. Telling us that war is hell (again) is rather counterproductive: hell is after all a rather interesting place, certainly more interesting than heaven, or civilian “normality”. Moreover, the quasi-religious, dramatic tone Swofford strikes of despair and ecstasy, loneliness and camaraderie, and the awful- but-fascinating baseness of war is not so different from that of Stone or Coppola (or for that matter, of Mailer). And while there are not quite so many explosions, there’s no shortage of pornography.

When sweating in Saudi in 1990 waiting for the war to start, Swofford’s unit find themselves being ordered to perform for the media, playing football in rubber NBC suits in 100-degree heat. To sabotage the hated propaganda op, they start a favourite ritual of theirs, a “Field fuck”, a simulated gang rape, “wherein marines violate one member of the unit,” Swofford tells us. “The victim is held fast in the doggie position and his fellow marines take turns from behind.”

Getting into the spirit of things, the jarheads shout out helpful remarks such as: “Get that virgin Texas ass! It’s free!” The victim himself screams: “I’m the prettiest girl any of you has ever had! I’ve seen the whores you’ve bought, you sick bastards!” The press stop taking notes.

Swofford reassures us that this practice “wasn’t sexual” but was instead “communal” – however, even in his own terms it seems that the distinction is almost superfluous: it’s the hallmark of military life that what’s sexual becomes communal. Elsewhere he tells us about the “Wall of Shame” on base: hundreds of photos of ex-girlfriends who proved unfaithful – frequently with other marines.

Swofford’s obsession with the marines had a media origin, beginning in 1984 when the USMC barracks in Lebanon was bombed, killing 241 US servicemen. He recounts watching the news bulletins on the TV and how he “stood at attention and hummed the national anthem as the rough-hewn jarheads… carried their comrades from the rubble. The marines were all sizes and all colours, all dirty and exhausted and hurt, and they were men, and I was a boy falling in love with manhood…”. Manhood in Swofford’s family was intimately linked to the military: his father served in Vietnam, while his grandfather fought in the Second World War. The desirability of manliness was the desirability of war.

It is probably not so strange that his obsession should have begun with an almost masochistic image of suffering and death: taking it like a man is an even more important part of the military experience than giving it. Sure enough, at boot camp Swofford finds his Drill Instructor to be a fully-fledged sadist of the kind that civilian masochists can only fantasise about: “I am your mommy and your daddy! I am your nightmare and your wet dream! I will tell you when to piss and when to shit and how much food to eat and when! I will forge you into part of the iron fist with which our great United States fights oppression and injustice!” Like many recruits, Swofford signed up to get away from a disintegrating home life and the flawed reality of his father and found that he had married his superego made barking, spitting, apoplectic flesh.

The DI’s job, as we all know from the movies, is to humiliate and break down the recruit, shame him, strip away his civilian personality and weaknesses and build him up into a marine. The DI is obsessed with inauthenticity: finding out who is not “really” a marine. He asks Swofford if he’s “a faggot… you sure have pretty blue eyes”. During one of these hazings, Swofford pisses his pants – an understandable reaction, but intriguingly it happens to be the same one that he mentions earlier in the book, when, as a young boy living in Japan (his father had a tour of duty there), he received “confusing and arousing” compliments on his blue eyes from Japanese women.

For good measure the DI also smashes Swofford’s confused shaved head through a chalkboard. Later, when this DI is under investigation for his violent excesses, Swofford shops him. However, he feels guilty about this and daydreams about running into the DI and “letting him beat on me some more”. Like I said, the USMC, God bless it, is a peculiar organisation.

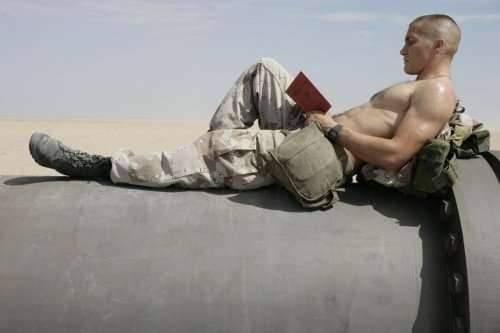

Of course, Swofford isn’t your average jarhead. “I sat in the back of the Humvee and read the Iliad” is a memorable line. Other days might see him buried in The Portable Nietzsche or The Myth of Sisyphus. Swofford also seems a little highly-strung: he attempts suicide, Full Metal Jacket- style, fellating the muzzle of his rifle after receiving a Dear John letter from his girlfriend. He’s saved by his returning roommate, who takes him on a run “that lasts all night”. More physical pain to salve the existential variety. By the book’s end, we are left with an image of Swofford, long discharged, wrestling with despair, not least over the sights he saw in action in Kuwait, but now without the distraction of physical suffering and discipline. Sisyphus without the rock.

Mind you, “jarhead” does suggest something that can be unscrewed: brains that can be easily spooned out. It may be true that some men become soldiers to kill; but it may equally be the case that some join to be killed, or at least escape the burden of consciousness. Swofford appears to feel cheated that life not only went on after the Gulf War (like most U.S. ground combatants he was a largely a spectator of the massacring potency of American air power) but in fact became more complicated and burdensome.

Under these circumstances, I think most of us would miss our DI.

HH: Interesting interview. I was watching an old Hollywood film the other night called ‘Air Force, a famous Second World War propaganda film. In it we see the ‘nips’ machine-gunning bailed-out US pilots in the air and on the ground. It’s presented as the ultimate barbarity by them, but as the interview shows, it was fairly standard practise on all sides. After all, it’s much easier to replace a plane than a pilot.

There’s no question but that Western civilians are fed a sanitised version of war – necessary myths that makes it easier for them to consider themselves as the ‘good guys’ and also to make it easier for war to be pursued by their governments. When I did basic infantry training we were taught how to make sure the ‘dead’ enemy were in fact dead. Kicking them in the balls was one way. It was pretty clear though unspoken that if they weren’t dead you might have to finish them off – battle lines move quickly and there often isn’t time or resources to spend on taking prisoners.

The latest manifestation of ‘necessary myths’ that make war more palatable to the public is the ‘no fly zone’. This sounds lovely and peaceful – but as in Libya it actually means bombing the crap out of anything that moves on the ground and quite a few things that don’t.

Recently heard author Tom Lewis interviewed on “Lethality in Battle”, and thought of this piece.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/lethality-in-combat/3862680

Get down and give me 50, you lousy maggot!!

As Boyd McDonald said, the USMC is the largest taxpayer funded SM club in the world.

Comments are closed.