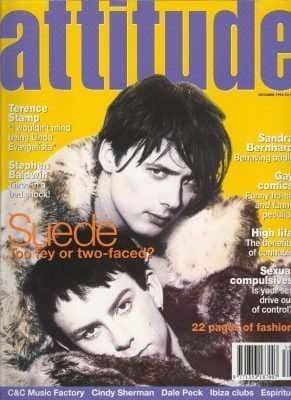

Mark Simpson rubs glam boy band Suede up the wrong way

(Originally appeared in Attitude, 1994 )

I have something to confess. When I listened to Suede’s eponymous debut album last year I was disappointed.

Disappointed that it turned out to be as good as the hype had trumpeted it to be. This was an album that went gold on its first day and sold 100,000 copies in its first week, by a group whose canny PR people secured them no less than nineteen magazine covers. Suede were everywhere, and everyone was hailing them as the greatest thing since The Smiths. So I’m sure you can sympathise with my frustration on discovering I couldn’t loftily dismiss them as paste imitations and actually had to admit that Suede, at once savage and tender, sleazy and sublime, was one of the greatest first albums ever.

Suede, the bastards, they had it all. They had the press; they had the material; they had the success. And to cap it all they had a dangerous, scandalous edge in the form of seventies androgyny queered up for the nineties. It was there in their songs—“We kiss in his room to a popular tune” (“The Drowners”); “In your council home he broke all your bones and now you’re taking it time after time” (“Animal Nitrate”)—and an album cover that featured two disabled lesbians snogging. Most of all, it was there in the sissy shape of front man Brett Anderson. With his irritating girlish fringe, weedy pointy shoulders, and pigeon chest, his swinging, childbearing hips (to which he insisted on drawing attention by banging the microphone against them), and his big-collared blouses baring a waspish waist and nibblesome navel, Anderson was the most offensively, delectably unmanly pop star since Morrissey. Damn him, damn them.

But I needn’t have fretted. Even as Suede were being feted, a backlash was brewing that would unmask them as fakes. What finally unleashed it was Brett’s remark that he considered himself “a bisexual who had never had a homosexual experience.” So Suede were frauds after all! All that mincing of hips and meeting of same-sex lips was phony, a sham! How satisfying.

Gay critics fired the first salvos, denouncing Suede as shameful exploiters of their culture. “Is there any real difference between what Brett from Suede is doing and what the Black and White Minstrels once did?” demanded one furious gay music journalist in Melody Maker.

Meanwhile, those straights who had been discomfited by the queerness of Suede, were given a green light to ridicule them for being big girl’s blouses, now that they had no fear of being called “homophobic.” After reading one gay critic’s attack on Anderson, “comedians” Newman and Baddiel included a typically witty sketch in their last tour that derided him for his poofiness.

Now, more than a year later, as Suede prepare to release their second album, Dog Man Star, they seem as cursed as they were blessed last year. Second albums are always a test, but after such a debut album as Suede, it becomes a trial. Gone is the honeymoon with the press, and gone also is Bernard Butler, the band’s guitarist and Marr to Brett’s Morrissey, in an acrimonious and very public separation. What does the Posing Sodomite have to say about that remark now?

“It was completely misread,” he says, the annoyance registering in his voice. “I was talking about the way I write and the way I generally feel about life. I don’t feel 100 percent akin to the male world or 100 percent akin to the female world. I was trying to express in a sexual perspective something that was more spiritual. Lots of things I write about are third person but written in the first person. Basically it was about not wanting to be pinned down.”

Brett Anderson is perched awkwardly on the arm of the sofa opposite, his body angled slightly away from me. Is he afraid of being “pinned down” as Someone Sitting on a Sofa? Is he, in fact, occupying some more artistic, ambiguous space between sitting and standing? Simon Gilbert, the band’s drummer, who came out as gay last year, is also here, facing me with his knees apart, apparently happy to surrender to the definite, fixed position of sitting on the sofa (albeit in the middle).

Brett continues in his fast-talking, surprisingly laddish South Coast voice: “I don’t think that anyone should have to be pinned down, even if they are definitely in a category—definitely gay or definitely straight. Because you happen to engage in certain sexual practices you shouldn’t have to be that and nothing more. I was trying to state something universal while everyone wanted to read something specific.”

He has a point. OK, so the refusing to be pinned down, “I-don’t- want-to-label-myself” thing is, in a sense, laughably adolescent. But isn’t that what pop is for? To be wilful, self-absorbed, self-important, pretentious? To refuse the definition, the certainty, the common sense, the maturity, the lifelessness of grown-ups? However hopeless such a resistance might be? But gays and straights did not appreciate Suede’s irresponsibility. Like most who advocate the possibility of a third position in the Sexual Identity War, Anderson was caught in the cross-fire between the two camps.

“The gay side thought it was a cop-out and the straight side weren’t happy with it either,” he complains. “Everybody wants you as a figurehead for their party: the world is just a series of tribes that want you to speak out for them but I’ve never felt myself part of any of tribe. I don’t intend to be a spokesman for any of them in particular. I’d like to think that individuals have got a bit more intelligence than to be happy with belonging to a glorified football team.

“I was seen as a whipping boy for people who wanted to be right-on as well. I happened to lay my defences open. Before I did people had thought: he probably is homosexual so we can’t criticise him on those grounds because we won’t be seen as right-on. Newman and Baddiel wouldn’t have dared do the same sketch about Andy Bell – although I’m sure they would like to – because they know they would have been slated as homophobic. I think men who are perceived to be gay but who aren’t actually don’t have the political defences to fall back on that gay men do.”

But then you were a rock star making this statement. Wasn’t it a rather cynical thing for someone in your privileged position to say, exploiting for your own ends the good old-fashioned “ambisexual” appeal of rock ‘n’ roll?

“Perhaps, but that would only be true if it were a charade. I think it would be impossible for me to act any other way. It’s not a ploy.”

So you refute the accusation that you were appropriating gay culture by “posing as a sodomite”?

“I wasn’t appropriating it – that sounds like stealing. I thought I had a kinship with it. My own sexuality aside, I’m quite deeply involved in the gay world because a lot of my friends are gay and because of this feeling of kinship. But like I said, I didn’t actually feel as if I was part of any particular group and didn’t want to be, so I didn’t feel a fraud at all. I wasn’t ‘posing as a sodomite’ – I felt completely justified in what I was doing.”

“I think it’s more to do with the way the press decide to portray us that caused the gay community to turn against us. In the NME there were cartoons representing us as limp-wristed Lord Fauntleroys. We weren’t trying to come across that way at all; that was the way the media decided to perceive us. Now I think we’ve gone beyond that – but that’s not to say that I’ve turned my back on what I was talking about then; it’s just the way my mind works.”

But surely you can’t just blame the press for your images as effete fops?

“Look, any pop band can get some success by wearing pink feather boas and some makeup – ‘Ohmygod, they’re outrageous‘ – we’re doing the opposite. We never felt we fitted into any categories. I think the music we make is a metaphor for everything including our sexuality, the way I’ve always tried to avoid barriers. Simon’s the same…”

“I have to say that I really sympathise with Brett’s position,” Simon chips in on cue. “I come from the other side of the fence if you like. I’ve called myself a bisexual person who’s never had a heterosexual experience. I never wanted to fit into the stereotypical image of what a gay person is. I think that it’s a lucky accident that brought me together with Brett because we really do share a similar outlook. Of all the bands I’ve been with, it’s only with Suede that I felt able to be honest.

“But I don’t want to be defined by my sexual preference, to be put in this category which is, to all intents and purposes, a clubby crowd. I never felt like I belonged in the straight world before I came out. After I came out I didn’t feel like I belonged in the gay world either.”

Actually, Simon doesn’t exactly look like he belongs in Suede. His hair – which is short, spiky, and an angry red-purple – is somewhat at odds with the louche Suede-boy coiffure. Apparently, people often think that he must be “the straight one” because he has short hair. As he continues talking, it becomes apparent where his image comes from. Like many young outsiders growing up in the late 70s, Simon had found a home in punk.

“It seemed to express something about me and I really enjoyed the ambiguity of the lyrics – like The Clash’s ‘Stay Free,’ which I interpret as a love song from one man to another. I’d never identified with politically gay bands and performers like Jimmy Somerville. I think that a song should speak to whoever’s listening without hitting them over the head with rhetoric that’s bound to turn some people off.”

But all the bands Simon had belonged to had displayed sufficient casual homophobia to persuade him to stay firmly in the closet. “They all had their puerile anti-gay banter which I had to sit through without saying anything. Suede were different. One day somebody asked if I was gay and I just said, ‘Yeah.’ For a moment I thought, Oh shit, what have I done? I’m out of the band now I fact, the way everyone reacted was brilliant. It felt so right .ill that. I think it has a lot to do with the similarity between his outlook and mine.”

Have either of you consummated your “bisexuality” since last year?

Simon: “No.”

Brett: “Not physically.”

Simon: “I’d say the same.”

What does that actually mean, though?

Simon: “It means that I can relate to a woman without actually getting into bed with her. In the same way as Brett does with men.”

So superficially there’s a neat symmetry between you in that you both want to avoid categorisation, aspiring to be something more and less than what you might be seen to be…

“… yes, there is …”

Simon: “. . . I’d agree with that. . .”

. . . but perhaps only superficially. Some might argue that you, Brett, were claiming a certain credibility without actually putting your iron in the fire or, probably more to the point, allowing someone else to put his in yours.

Brett: “Mine’s a kind of active statement and Simon’s is a kind passive statement? Yeah, I know what you’re saying. There’s a huge history here which I’m kind of attaching myself to, or port assume I’m attaching myself to. I don’t really see how to get away from it—I’m not saying that I never said it, but….

Now Brett is swallowing water. I throw him a line: Perhaps you were attacked for merely putting into words what has been the unofficial formula for truly great rock ‘n’ roll all along?

“Yeah, I’d agree with that.”

Does he think that his crime was more explanation than exploitation?

“Yes, I think that’s been my problem all along—giving too much away. It would have been very easy for me not to mention my sexuality at all and people would draw their own conclusions. I’ve been incredibly honest. I’ve never said anything that wasn’t true.” As a result of Brett’s honesty, some sections of the indie press slated Suede for being “inauthentic” poseurs—possibly the worst crime in the indie universe. Perhaps this had something to do with the notion among some sections of the music press that masculinity is equivalent to authenticity, and both are equivalent to working classness?

“Yeah,” Brett agrees. “Indie does have this huge emphasis on authenticity: everyone has to play and it’s a case of all the lads together. But the whole indie thing is so much a fucking fake itself!” he exclaims with real vehemence. “It’s actually the children of the landed gentry with guitars! I can name quite a few names—but I won’t—people with extravagantly rich parents who have decided to go for this scruffy image.

“None of us have ever been part of that sort of gang at all. We made music from the other direction: we’re from a scruffy background and aspired to something much more . . . ambitious. I’ve always wanted to make pop music; I’ve always wanted to have hits; I’m always had a really pop ethic and loved the bands who were out-and-out Motown. These other people are the reverse: they’re coming from successful backgrounds and want to have this authenticity and avant-garde appeal by slumming it. I want to make pop songs that everyone can understand and really . . . shine.”

This is the moment to mention those lovable dog-racing cock-er-nee geezahs (or so they’d like you to think) who have risen to fame since Suede’s disappearance from the scene. Brett pauses at the sound of their name-—maybe bristles would be a better description. “Ummmm … I don’t really have anything to say about Blur.” He looks at Simon.

“No, there’s not much to say,” concurs Simon, almost spontaneously. “A lot’s been made of our supposed spat with them but it’s all crap really.”

Brett: “They do their thing and we do ours. The press make out that there’s this big rivalry between us, when there isn’t really.”

I try to explain that all I want is a kind of “compare and contrast” angle on Blur. Brett shifts uneasily, moving even more of his body line away from me, flicking nervous sideways glances in my general direction, head close to his chest as he speaks—like a painfully shy boy making his first pass, or telling the police where he hid the body.

“Look, any of these bands that have been getting all this attention lately have made it because we haven’t been around [flick]. That sounds really big-headed I know, but I don’t think that anyone has had the track record that we’ve had. Most people only know our singles—that doesn’t reveal the depth to our musical style [flick]. Things like our B sides. We’ve never made a duff B side. Some of our B sides are better than our album tracks. Without being really, y’know, conceited [flick], I don’t think that there’s anyone who has produced such a body of work in such a small amount of time. Not even some of the great British groups of the past [flick, flick], I think that the next album will completely ground everyone else [flick]. I think.”

His speech over, Brett shifts his bony bum around on the sofa arm a teensy bit more towards me.

“I hate all this big-headed crap, y’know?” he confesses. “‘We’re the greatest,’ blah, blah. We’ve never gone around with this attitude”—now his voice is almost plaintive—”we just happen to think that our music is great and that it has real depth to it.”

Did he face away from me because he was embarrassed at having to sell himself; or was it because he was embarrassed by the “real” Brett Anderson—someone fiercely ambitious, competitive, and egotistical? Whatever the reason, there’s more than a certain amount of truth in what he’s saying. It wasn’t until Suede came along and showed that the body of pop wasn’t quite as cold as everyone had taken it to be that groups like Blur had any chance at all.

The few tracks I’ve heard off the new album suggest Suede have indeed taken a new direction. Toned down is the raw energy of the first album; anger is here replaced by melodrama, and, astonishingly, it comes off. Emotions are painted on a larger canvas with more unabashed extravagance than British pop has had for years. Some will denounce it as self-indulgent and pompous. But at least one track, “Still Life”—a ballad that grows into a breathtaking orchestral production—is going to be huge. It’s so expansive, so gorgeous that no one will be able to resist its goosepimpling embrace. It will be played on Radios 1 and 2; housewives will hum distractedly to its bittersweet melody in kitchens while their sons weep disconsolately to its wailing angst in their bedrooms.

“I think that we’ve successfully combined those things which we’ve always been good at before,” claims Brett. “We’ve always been able to produce those bubblegum singles like ‘Animal Nitrate’ and ‘The Next Life,’ and on this album we’ve been able to blend the cockiness of these with something more wistful. ‘Wild Ones,’ for example, is for me the most successful thing I’ve ever written. It’s incredibly catchy and poppy and at the same time, it’s something quite beautiful. I think,” he intones solemnly, “it’s really, really rare for pop music to produce something beautiful.”

Do I detect something of Ravel’s Bolero in the finale of “Still Life”?

“Yeah, we ripped it off a bit. If people just heard that track off the album they’d be quite misled because it is very orchestral. We wanted to go for something quite heroic. It’s very easy for a pop band to get a bit of money and pay for an orchestra to accompany them. I think that song justifies it because if you hear it on its own, as an acoustic vocal, it builds naturally anyway. The orchestral embellishments just suggest themselves.

“It is quite pompous, especially the end part. But pop music has always been about being pretentious—you can’t be worthy; there’s no point. That’s the crappy thing about the indie scene: it doesn’t go any further than a bunch of people slapping each other on the back going, ‘Yeah, that’s worthy.'”

Like the Manic Street Preachers, Suede are a pop group, who have that loyalty to pop music that most fans don’t have time for any more. Suede are from an era where there were only three TV channels; two were showing football and one was showing a documentary on fly-fishing. They are from an era of youth-club discos and smoking behind the bike sheds, when the idea of a good time was rattling around in a battered Cortina without tax or insurance, or beating up the local queer. It’s also an England that arguably no longer exists or, if it does, is fast fading away.

Simon disagrees. “Since I came out, I get a lot of letters and I can tell that life in small towns hasn’t changed much. People tell me about getting beaten up in the school playground and stuff. Mind you, Stratford, where I grew up, is really weird. The first time I went back to Stratford after coming out I expected people to be really put off about it—y’know, ‘Oh, here’s that fuckin’ queer.’ But not at all. People were saying, ‘Why didn’t you tell us when you used to hang around with us? It would have been cool.’

“It’s easy to say that things have changed sitting here in London as a member of the media elite. This world just carries on and on, no matter that there are smart people walking around with black briefcases. [Brett glances at my black briefcase.] There are kids out there who desperately need something to cling on to. Yeah, it is an old- fashioned idea, but it’s what we grew up with. I think it’s easy to talk about the advancement of society when you live in a big city, but I don’t think things have moved on from 1954 once you get outside it.”

But isn’t this a rather patronising view?

“Yes, it is quite patronising, but I also think that it’s quite true,” he says rather impatiently. “It’s patronising towards the people who inflict it on the ones who don’t want it. But they deserve it. Like all my family. They’re living in a different age. It’s all lino and corned beef, like something out of Look Back in Anger.”

Brett and Simon grew up in those corners of Britain where Thatcherism, satellite TV, and Sega Mega-Drives never happened. For Simon it was the tourist/rural limbo of Stratford-upon-Avon; for Brett it was Haywards Heath, a dormitory town north of Brighton. Both men wanted to be pop stars for as long as they can remember. “When I was about four I used to imagine being Paul McCartney,” confesses Simon. No wonder he became a punk.

I put it to Brett that yes, Britain is still dowdy and desperate—perhaps more so—especially in those forgotten corners. But the world that produced a passion for pop has gone.

“Yes, that’s true—the world has completely changed in that sense. That’s why I think the new album is a step forward because it is not as caught up with the inverted nostalgia. Where the last album was retrogressive; the new album is much more wistful and in love with the modern age.”

Brett admits, however, that his new optimism is somewhat stifled by certain local realities. “The Suede backlash was partly to do with a reaction against success. Anyone in this country who achieves success is struck out against. You’re allowed to go only so far and no further. This or that song will be dismissed as a ‘pile of shit’ because it’s not avant-garde enough, not because it’s actually any good or not. America’s very different—it seems to be more hopeful.”

But isn’t that part of the deal? That the melancholic, repressed twistedness that your music has fed off can’t be separated from the bitterness, envy, and narrow-mindedness?

“Yes and that’s where the dichotomy lies. This band is caught up in its own history and that’s what makes us what we are. Yet there’s that desire to reach a kind of spiritual state and shed your skin and go on to another plane . . .”

Isn’t this where you end up following in Morrissey’s steps, someone who also celebrates the mundane and the desperate in British-ness and yet tries to transcend it?

“I don’t think he’s expressed any desire to escape it,” replies Brett quickly. “After fifteen years in the music business there’s been no development in his intention, and I intend to develop. He’s found his niche and seems content within it. That’s fair enough; that’s the way he feels. I don’t want to come across like that. We want to do different things, and even over the space of the last two albums, I think we’ve made quite giant leaps.”

Brett seems rather keen to put some distance between himself and Moz. Maybe this is because he was mocked by the Glum One himself for his hero worship of Bowie and Morrissey. (Morrissey reportedly said, “His reference points are so close together that there’s no space in between.”)

But talking of “giant leaps” actually encourages the comparisons. The world gasped at the recent discovery that Morrissey liked a game of footie and now I can exclusively reveal that Brett was good at sport at school.

“Sport was the only thing I did. I held the record for the 800 metres at my school, Oat Hall Comprehensive, for five years,” he says in a studiously casual way, obviously enjoying the turbulence this fact creates in the wake of his Prince of Fey image. “They used to feed me a special high protein diet at school because I was the only one good at sport.”

Simon was not such a prized pupil. “I hated school for the first year but then I became a punk and got respect—perhaps because I was the only one in Stratford. I wasn’t any good at sport but I was very good at forging my mum’s handwriting on the off-games chits.”

Just before the end of the interview I ask Brett about his relationship with pigs. References to things porcine abound in his work, including the track “We Are the Pigs” on the new album. What do porkers mean to him?

“I don’t know really,” he says looking away with a half-smile on his face. “The cover of Animals by Pink Floyd is probably one of my favourite images in the world. It’s a metaphor for sexuality and brutality, stuff like that.”

I suppose that pigs are very . . .

“Human.”

Yes . . .

“And pink.”

Absolutely. And in touch with their bodily functions.

“Yes. They’re supposed to smell but they don’t.”

And so the truth is out at last: Brett’s thing for pigs and pig culture is not so much exploitation as identification.

Download It’s a Queer World

That Newman & Bladdy’ell sketch was ripping the piss out of Brett for trying to project a “Gayers – on your side!” image but coming across like a comic stereotype of a “poofy” gay man instead. Targeting Andy Bell wouldn’t be the same as his stage persona is an extension of his *innate* non-macho gayness. It was more than just being a ’70s style whoopsie for the benefit of a hetero audience, and definitely many more rungs up the ladder from recent atrocities like Al Murray’s Gay Nazi.

From the ever-reliable Wikipedia entry for the album:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dog_Man_Star

‘Anderson spoke of the album’s title as a kind of shorthand Darwinism reflecting his own journey from the gutter to the stars. Fans noted the similarity to experimental film-maker Stan Brakhage’s 1964 film, Dog Star Man. “The film wasn’t an influence but I obviously dug the title,” the singer later confessed. The title is intended as a proud summation of Suede’s evolution. “It was meant to be a record about ambition; what could you make yourself into.”

‘The artwork, which features a naked man sprawled on a bed were lifted from one of Anderson’s old photo books. Taken by American photographer Joanne Leonard in 1971, the front cover picture was originally titled “Sad Dreams On Cold Mornings” and the rear photo “Lost Dreams,” Anderson says, “I just liked the image, really, of the bloke on the bed in the room. It’s quite sort of sad and sexual, I think, like the songs on the album.”‘

what’s the origin of the title “dog man star”? A reference to the american experimental filmmaker brakage? All the hip art kids in college would talk about Dog Star Man as a must see that they couldn’t stand.

They clearly try to add more culture or Culture to pop than you get from the indie scene or ever will, but they evoke, I’m sorry to say, Andrew Lloyd Weber and Boccelli, when they stray too far from the successful bowieism (I don’t think an artist can ever be categorized, no matter how flatteringly, without seeming “derivative” and plagiarist – they ALWAYS have to be called to an original genius, for people to accept them at all).

And in “still life” and “we are the pigs”, they’re folk rock and jazz inspired, struggling to fit into indie’s droning death (soft guitar underlying the requisite electric riffs, wandering melody). I feel like I want to protect them. But with things so much smaller and more tolerant now, they don’t need protection.

Also, they’re not metrosexual. Too sensitive, too rough around the edges. Too thin. Too meaningful. Too tough. Too pale.

Now I wonder, does that mean the new sexuality is devoid of pretension?

His voice is as grating as the general pretentiousness – but somehow all the more appealing to me for that. There’s usually a lot of echo on it, like he’s singing in an estate lock-up. Which is probably deliberate.

Comments are closed.