Mark Simpson on the almost-forgotten ‘English Whitman’

On his 80th birthday in 1924, five years before his death, the socialist Utopian poet, mystic, activist, homophile, environmentalist, feminist and nudist Edward Carpenter received an album signed by every member of Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Cabinet. Glowing tributes appeared in the socialist papers as well as the Manchester Guardian, the Observer, the Evening Standard and even the Egyptian Gazette.

He was hailed by the philosopher C.E.M. Joad as the harbinger, no less, of modernity itself: ‘Carpenter denounced the Victorians for hypocrisy, held up their conventions to ridicule, and called their civilisation a disease,’ he wrote. ‘He was like a man coming into a stuffy sitting room in a seaside boarding house, and opening the window to let in light and air…’.

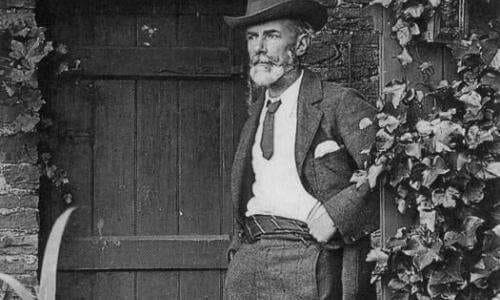

In the early Twentieth Century Carpenter was a celebrity, a hero, a guru, a prophet, a confidant: an Edwardian Morrissey, Moses and Claire Rayner in one. Multitudes of men and women – but mostly young men – had beaten a path to his door in his idyllic rural retreat-cum-socialist-boardinghouse in Millthorpe, near Sheffield to sit at his vegetarian, be-sandled feet, or take part in his morning sunbaths and sponge-downs in his back garden.

Soon after his death, however, his charismatic reputation faded faster than a Yorkshire tan. By the middle of the century, he was the height of fashionability, and regarded by many on the left as a crank. When that manly Eton-educated proletarian George Orwell decried the left’s habit of attracting ‘every fruit juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, “Nature Cure” quack, pacifist and feminist in England’ everyone knew whom he was dissing.

Today very few would. Despite his extensive writings, despite the way many of his causes and indeed much of his lifestyle have become mainstream, and despite the brief renaissance of his works with the gay left after the emergence of gay lib in the 60s and 70s – a movement which he appeared to predict – and a hefty, worthy and yet also fascinating new biography by the feminist historian Sheila Rowbotham (Edward Carpenter: A Life of Love and Liberty; Verso) notwithstanding, it sometimes seems as there’s almost nothing left of Ted, as his friends called him, save his beard and sandals (he appears to have introduced sandal-wearing to these shores). He’s become the Cheshire cat of fin de siècle English Utopianism. In fact, one could argue, and I will, that the thing that connects most of us with Carpenter today is EM Forster’s arse.

George Merrill, Carpenter’s uninhibited Sheffield working-class partner touched Forster’s repressed Cambridge backside during a visit to Milthorpe in 1912:

‘…gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most peoples. The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long-vanished tooth. It was as much psychological as physical. It seemed to go straight through the small of my back into my ideas, without involving any thought.’

Inspired by Merrill’s tykish directness, Forster, went home, sat down on his probably still-tingling buttocks and wrote the first ‘gay’ novel Maurice, which famously featured a love-affair between Scudder the sunburnt and impetuous groundsman Alec and the uptight, middle-class Maurice. Though it wasn’t to be published until after terminally timid Forster’s death, DH Lawrence saw the manuscript and was himself touched: Lady Chatterley’s Lover is in many ways a heterosexualised Maurice. And of course, when Maurice was made into a film in the 1980s starring James Wilby and Rupert Graves succeeded in making millions of rumps, male and female, tingle at a time when homosexuality, as a result of Section 28 and Aids had become a major cultural battleground.

Before Merrill, Edward Carpenter’s buttocks had been touched by the American sage Walt Whitman and his passionately romantic poems about male comradeship, frequently involving working men and sailors, whom he travelled to the US to meet (though it is unclear whether here the touching was literal or metaphorical). Carpenter became a kind of English Whitman figure, though more outspoken on the subject of toleration of same-sex love than Whitman ever dared to be in the US – if not, alas, nearly as fine a poet (another reason why his work hasn’t endured).

Lytton Strachey decreed sniffily that Alec and Maurice’s relationship rested upon ‘lust and sentiment’ and would only last six weeks. Whatever Merrill and Edward Carpenter’s relationship was based on – and Robotham argues that it was rather complicated and not what it appeared to be – it lasted nearly 40 years and was an inspiration to many.

Carpenter was nothing if not sentimental, when he wasn’t being just patronising. He described Merrill as his ‘dear son’, his ‘simple nature child’ his ‘rose in winter’ his ‘ruby embedded in marl and clay’ and delighted in Merrill’s lack of guilt about ‘the seamy side of life’. Raised in the Sheffield slums and without any formal education Merrill was almost untouched by Christianity. On hearing that Jesus had spent his last night on Gethsemane Merrill’s response was “who with?”

It was Merrill’s – and the innumerable other working class male lovers that Carpenter had both before and after meeting him – lack of ‘self-consciousness’, or perceived lack of it, that attracted Carpenter, who was born into an upright upper middle-class family in Hove, Brighton (and it was his sizeable inheritance that financed his purchase of Milthorpe and his comradely life in the North). He was drawn to the working classes because he saw them as rescuing him from himself – as much as he was rescuing them.

‘Eros is a great leveller’, Carpenter wrote in The Intermediate Sex. ‘Perhaps the true democracy rests, more firmly than anywhere else, on a sentiment which easily passes the bounds of class and caste, and unites in the closest affection the most estranged ranks of society’. He observed that many ‘Uranians’ ‘of good position and breeding are drawn to rougher types, as of manual workers, and frequently very permanent alliances grow up in this way.’

It’s worth pointing out that even Wilde and Bosie’s relationship, which was to cause Forster and many other homosexuals at that time such grief, was based on their mutual enjoyment of rent boys. Carpenter disapproved of such exploitation, but it’s not impossible to imagine Wilde, or one of his characters, jesting that people like Carpenter were socialists only because they didn’t want to pay for their trade.

Robotham to her credit doesn’t shrink from pointing out the limits of Carpenter’s socialism: ‘Carpenter never queried his own tacit presumption that the lower classes and subordinated races were to be defended when vulnerable and abject but treated with contempt when they sought individual advancement.’ To this it could be added that if Carpenter succeeded in abolishing class, then with it would be abolished the interest in the working classes of men like Carpenter. Each man kills the thing he loves.

What though was working class youth’s interest in Carpenter? In a word: attention. It seems they were flattered to be singled out and treated with casual equality by a gent, and an attractive, charming one at that. One young lover wrote of Carpenter: ‘You feel inclined to get hold of him as a boy would his mate’ and talked of his ‘Handsome appearance – his erect, lithe body, trim and bearded face, penetrating eyes and beautiful voice.’ Carpenter was to continue attracting young working-class men to his door well into silver-haired old age.

Carpenter had a contradictory view of homosexuality, seeing those exclusively attracted to their own sex as psychically androgynous ‘intermediates’ like himself who were ‘born that way’ – but also as harbingers of a new age, the cultural ‘advance guard’ of socialism in which a Utopian androgyny would be the norm. Not everyone shared his enthusiasm for a future world of Carpenters. George Bernard Shaw for one was enraged by the idea that ‘intermediacy’ should be recommended to ‘the normal’ as the desired way to be.

EM Forster described Carpenter’s mysticism as the usual contradiction of wanting ‘merge with the cosmos and retain identity’ at the same time. This in fact described pretty much everything, from Ted’s attitude towards comradeship and homosexuality, class, and socialism, and even Millthorpe where he would write standing in a sentry box he had built in his garden while his ‘retreat’ was overrun by guests.

His championing of androgyny and female emancipation also had contradictions. Robotham describes his horror and disgust at the androgyny of a Siva statue he witnessed on a mystical visit to India as being ‘akin to the disgust he had felt at seeing the female nudes in a French art gallery…’. For Carpenter, ‘acceptable femininity consisted of lithe gay men and supportive, tom-boyish sister figures.’

Carpenter’s works were taken up by the gay libbers and New Left in the 60s and 70s partly because of his rejection of male and female sex-roles and also because of his proto-gay commune lifestyle in Millthorpe, with his open relationship with Merrill (and also several local married men). For Carpenter, the personal was political long before it became a lapel button.

But in the 1980s gay lib was replaced by gay consumerism, ‘intermediates’, particularly many working class ones keen to advance themselves, turned out to be the vanguard not of a back-to-basics socialist Utopia but of High Street Thatcherism. The mainstreaming of ‘lifestylism’ happened largely because it was divorced from politics – and Carpenter – and became about shopping. Which would have horrified Ted who had an upper middle-class disdain for ‘trade’ (the shopkeeping kind). Lord only knows what he would have made of the consumerist androgyny of the metrosexual.

Perhaps the most lasting and pertinent thing about his life is a question: How on Earth did the old bugger get away with it? How did he avoid a huge scandal? How did he end up so lionised in his old age? Especially when you consider what happened to Wilde?

The answer is probably the same reason for his lack of appeal today. His prose now seems often strangely precious and oblique and replete with coy, coded classical references. Worst of all for modern audiences, he necessarily downplayed the sexual aspect of same-sex love. His most influential work Homogenic Love, published in 1895, the first British book to deal with the subject of same-sex desire as something other than a medical or moral problem, rejects the word ‘homosexual’ ostensibly on the grounds that it was a ‘bastard’ word of Greek and Latin, but probably because the Latin part was too much to the point.

Class helped too: when the police threatened to prosecute some of his works as obscene, he was able to scare them off with an impressively long list of Establishment supporters. Even his live-in relationship with Merrill was often seen as one of master and servant (and in fact that’s how Merrill, who was financially dependent on Carpenter, was legally described).

ESP Haynes suspected that Carpenter might not be as simple as he presented himself, that his mysticism ‘gave him a certain detachment which protected him against prosecution as a heretic’. To which Rowbotham drily remarks: ‘As for the non-mystical Merrill, he just tried out the idealistic admirers’. (Or as that other Northern vegetarian prophet Morrissey was to sing many years later: ‘I recognise that mystical air/it means I’d like to seize your underwear.’)

Whatever Carpenter’s survival secret, it’s rather wonderful for us that he did, and although his haziness may be part of the reason he fades in and mostly out of consciousness today, as Robotham concludes her sympathetic yet clear-eyed study: ‘One thing is certain, this complicated, confusing, contradictory yet courageous man is not going to vanish entirely from view.’

(Independent on Sunday, 5 October 2008)

Yewtree: Thanks for the background info. I’ve not read ‘Triumph of the Moon’ but will look it up.

HH: I think the gay libbers in the 60s and 70s made a point of practising ‘free love’, and may even in some cases have frowned upon monogamy as bourgeois. They may have been right.

But I don’t think I’d make a very good gay hippie. My toes look atrocious in sandals.

“But in the 1980s gay lib was replaced by gay consumerism… The mainstreaming of ‘lifestylism’ happened largely because it was divorced from politics…”

I wonder if it isn’t time for us mainstream “lifestylist” homosexuals (and I count myself among them) to rediscover a bit of old-time hippie-style gay lib.

It might help sidestep a lot of the pointless arguments about biological destiny—if it feels good for two people, they should do it, whatever their motives, or the proximate cause.

On the other hand, if one of the defining characteristics of heterosexual hippiedom is the abundance of free love, then many gay men are practicing hippies already, independent of their philosophical outlook.

Sexual disinhibition, in a male homosexual environment, has never quite held the taint of political radicalism in the same way Carpenter’s appears to have done. Or has it?

Carpenter also had a massive influence on the early development of the Pagan revival, though sadly his contribution is largely forgotten today – fortunately he is mentioned and quoted in Ronald Hutton’s excellent book, “The Triumph of the Moon”. Likewise Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, another gay Pagan who is largely forgotten.

Harry Hay (founder of the Mattachine Society) was a fan of Carpenter too.

Comments are closed.