Mark Simpson reviews David Fraser’s ‘Frederick The Great: King of Prussia’

Frederick, like a lot of ‘greats’, has some dodgy fans. Most famous of course is his historical stalker Adolf Hitler, who hero-worshipped the general king who established Prussia as a first rank power, and saw himself, as really scary fans do, as his true heir.

And in fact, the unmarried Austrian corporal’s military and diplomatic genius did manage to arrange for a Twentieth Century replay of Frederick’s heroic Eighteenth Century battle against a combination of most of the major European powers (Hitler’s masterstroke consisted in the truly inspired addition of the United States to the list of opponents ranged against him). As we all know, Adolf the Shortarse’s reign achieved the opposite results to Frederick the Great’s: abject defeat, devastation on a scale unimaginable in Frederick’s time, partition, and a Berlin occupied by Russians.

And then there are Frederick’s other ‘dodgy’ bachelor fans who wish to claim him for their cause. After all, he spurned the affections of his wife Wilhelmina, he sired no children, women were almost invisible at court, and his name was not linked with famous mistresses as most other princes of the period worth their codpieces were. Instead, he collected statues of Antinous, Hadrian’s lover, and Ganymede, and ‘was known to caress, tickle, pinch the ear of some favoured page’.

So, it is entirely understandable and even commendable that David Fraser, a former General in the British Army should want to save Frederick from both these kinds of Fans of Freddie in his major biography Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. After all, Hitler and, until very recently, homos were two things the British Army knew it was against. However, Fraser’s brusque dismissal of both these kind of claims in the early part of his authoritative, impressive, if occasionally gruelling tome Frederick the Great, is not entirely convincing. He claims that because Frederick was an Enlightenment man, cultivated and an aesthete, he could not therefore be any kind of progenitor of Nazism – but then, as Theodor Adorno argued, Nazism was not so much anti-Enlightenment as the Enlightenment’s dark side. Besides, Hitler was an architect, a painter and the author of a philosophical treatise called Mein Kampf (he was a terrible philosopher and a mediocre artist; but then, Frederick was a mediocre poet).

More generally, it could be pointed out that Hitler was much more of a continuation of Prussian ideals and goals than is comfortable for many Germans to admit – now. Hitler’s extremely popular – until it brought the Red Army to Brandenburg – policy of ‘lebensraum’, which aimed to annexe the Ukraine and much of European Russia and which was the motive for his preemptive war against France and Britain, was not a Satanic Nazi invention of his but a continuation of the goals of (largely Prussian) Officer Corps of the First World War. Which in turn was of a piece with the Greater Germany created by Prussia’s expansionism under Bismarck.

With respect to the rumours of rum bum goings on, Fraser acknowledges the ‘homosexual’ reputation Frederick has gained, outlines his lack of interest in the fair sex and admits that this ‘together with his unabashed aestheticism and the delicacy of his tastes… gave plausibility to his alleged impotence or homosexuality.’ (The two, of course, being interchangeable). He also admits that their were rumours that Frederick enjoyed what Fraser calls the ‘pathic’ role in sodomy (looking up ‘pathic’ in my dictionary I discover, with a thrill, it means ‘victim’ or ‘catamite’ – presenting an irresistible chat up line: ‘are you active or pathic?’). In the end, however, Fraser is unconvinced and claims that Frederick was probably asexual, or at most a non-practising sodomite. And then moves smartly on to the business that really interests him. War.

Now, while it is certainly refreshing in an era when everyone, especially historical figures, have to be interpreted and interpolated according to whether their nether regions pointed East or West, to find someone much more interested in the battle order of Frederick’s Regiments than his bedtime antics, Fraser doesn’t really get away with it. In fact, as with the other Fans of Freddie already mentioned, it does seem here as if we’re learning more about Mr Fraser’s foibles than King Frederick’s. As, for example, in the passage where he cites, as evidence against Frederick’s alleged ‘homosexuality’, the fact that he bought some erotic paintings featuring five pairs of ‘male and gloriously female lovers’.

Especially since, a little later, our sceptical author seems keen to suggest that, despite his philosphe inspired distrust of superstition, Frederick did have some religious beliefs – when there is considerably less evidence that Frederick was attracted to the idea of a Deity than he was to the idea of sodomy. As Fraser puts it himself: ‘prejudice has too often clouded perceptions of one of the most extraordinary men ever to sit on a throne or command an army’. Fraser is, of course a Fan of Freddie too. However, aside from the relatively minor lapses already mentioned, he isn’t a dodgy one, but for the most part a fairly objective ‘straight’ one.

Frederick proffers fertile material for some of the psychological speculation which Fraser eschews. He was terrorised by his father Frederick William ‘the soldier king’ who beat him and declared he was ‘not prepared to tolerate an “effeminate creature, with no manly inclinations,” who… was uncleanly in his person and wore his hair long’ (of course today these latter two habits would be categorical proof that Frederick wasn’t gay). A young Frederick tried to escape Prussia to England but was caught and imprisoned by his father, after being forced to watch his best friend ‘whom he probably loved’ being beheaded. Which would be enough to turn any lad a bit odd, and maybe even into a military genius (there are some interesting parallels here with Alexander whose warlike father Philip was also a tyrant who tormented his son – a son who also went onto to surpass his father’s considerable military achievements and gain a reputation for ‘pathic’ behaviour). As Fraser puts it, Frederick came to manhood ‘in frightful circumstances, circumstances which would plead for understanding had he subsequently become a criminal, a degenerate or a lunatic rather than, as happened, a genius.’

Certainly, that criminal, degenerate, lunatic Voltaire thought Frederick was a genius, or at least a ‘philosopher king’. He also described him as ‘the Solomon of the North’ and ‘the hope of the world’. And it wasn’t just because he had received a very large Burgandy bill that week. Frederick was a Fan of France; he hated German and spoke it ostentatiously badly, preferring to speak and write in French, frequently dropping the ‘k’ from his name in signatures to Francify it. He hero-worshipped Voltaire and they exchanged countless effusive letters in verse in which they attempted to flatter one another to death. Voltaire was even invited to move to Berlin and was awarded a house and a fat pension (Rousseau was made a similar offer, but made the mistake of asking Frederick, in the fashion of some do-gooding Hollywood celeb: ‘what was being done for those who had lost limbs in his service’). Frederick eventually discovered the downside to French intellectuals: ‘he has the malice of a monkey,’ he declared exasperatedly after another scandal erupted involving Voltaire’s greed and heinousness, ‘but I need him for my French studies.’ Voltaire was eventually sent packing and, characteristically, he offered his services to Maria Theresa of Austria, Frederick’s archenemy. (To her credit she rebuffed him saying: ‘Voltaire belongs not in Vienna but on Parnassus’)

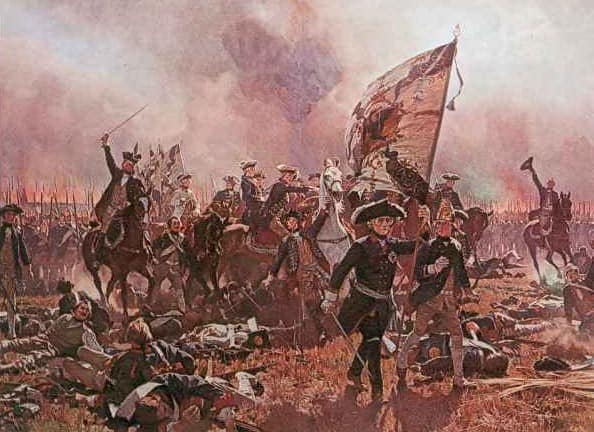

For all the exhaustive, often dramatic and always conscientiously detailed accounts of Frederick’s exemplary career on the battlefield offered here, dashing around Prussia fending off the Russians in the North, the Austrians in the South, the French in the West (and getting his horse shot from under him several times an hour, it seems), it is through Fraser’s account of Frederick as a ruler, or ‘Solomon of the North’ that Frederick’s genius – and his modernity – is grasped by the civilian. Frederick, who frequently claimed to loathe soldiering, understood the importance of tolerance, for personal as well as political reasons. Against the custom for scorn, he defended an unmarried female servant in his household who had become pregnant. In Silesia, which had a large Catholic population, a Catholic soldier was convicted of stealing jewels from a statue of the Virgin in a Church. The soldier claimed, cannily, Mary had given them to him. Frederick assembled some theologians and asked them whether Our Lady could do such a thing. They concluded that it was improbable but not impossible. Frederick annulled the sentence. He had, he said, no power to forbid Our Lady from giving. But, he added, he would in future punish with death a soldier or anyone else who accepted such a gift.

Frederick’s sense of justice was remarkably democratic for an absolutist monarch. A distinguished French traveller struck a postilion, who hit back and threw him out of the carriage with his valise. The Frenchman, as Frenchman do, wrote indignantly to Frederick – who told him to be less free with his whip in future. ‘What an infernal country this Prussia is,’ complained the Frenchman, ‘where you cannot thrash a postilion without bringing blows on yourself!’ Frederick’s tolerance might have been a desire to prove his intellectual as well as his temporal mastery. In a precursor of Stalin’s famous question about how many divisions does the Pope have, Frederick was given reports of a man in Berlin who called him a tyrant and was proposing treason. “What resources has this man?” asked Frederick. “Can he raise an army of 200,000?” “No, sire,” came the reply. “He is poor, a private individual” “Well,” laughed Frederick, “that’s all right!”

Not even a philosopher king can master his legacy, or his followers. Another Fan of Freddie’s, after routing the Prussians decisively at Auerstadt and Iena in 1806, visited his tomb at Potsdam. “Hats off messieurs,” Napoleon commanded his generals. “If he were alive we would not be here.”

Indeed, but on the other hand, it’s not entirely fanciful to speculate that if Frederick hadn’t lived, Napoleon might not have come.

(Independent on Sunday, Feb 20, 2000)

I have to admit that reading those old lists “inverts” and “uranists” used to make about who was gay or not, has always made me think “Are you trying to put us off homosexuality or what?” Being of German background myself, Alt Fritz always seemed to set a bad precedent… Although nobody has ever told me that I would look ‘cute’ in a 18th century uniform, like they did with the Nazi outfits!

He was an accomplished flute player, and to paraphrase the composer Ned Rorem, ‘100 percent of flute players are gay’.

Comments are closed.