Mark Simpson is mystified by the aim of a book that obscures its author’s own status – and anxiety

(Independent on Sunday, 07 March 2004)

‘Oh, god! Alain de Botton! Do you know how rich his family is?! His dad owned Switzerland!!”

This, or something very similar, is what almost every fellow scribbler exclaims when this “popular” philosopher’s name is mentioned. Which is rather frequently, because Mr de Botton, damn him, is a bestselling author whose books get made into TV series. In their eyes, his crime is two-fold: in a world where most writers find making a grubby living a terrible, degrading struggle, a living and more has already found de Botton. Even worse, he appears effortlessly to command riches, attention and respect on his own account when he doesn’t need them.

I have no idea how much inherited wealth Mr de Botton does or does not have at his disposal, but a glance at the press cuttings reveals that his late father, Gilbert de Botton, owned a successful investment company which was sold in 1999, a year before his death, for £421m. His step-mother, Janet (née Wolfson) is an influential collector of modern art and heiress to Great Universal Stores: she was recently listed by The Sunday Times as the 12th richest woman in the UK, just after the Queen and four places above Madonna.

Now, mentioning any of this is terribly vulgar I know, especially when talking about a man who has staked his own claim to fame and status on being – as his jacket blurb describes him – “genuinely wise and helpful”. Someone who, moreover, gives every impression of being incredibly nice and incredibly embarrassed, if not actually apologetic, about their privilege and success. Nevertheless, I feel in my unhelpful and unpleasant way that this tastelessness is rather germane to a book called Status Anxiety.

Precisely because the author is such a polite, learned and charming writer with a fine appreciation for history, literature and the arts which he is so very generously keen to share with us, he never explicitly touches on the subject of his own status, or his own anxiety about what the world thinks of him. Despite the fact that he must be entirely and painfully aware of exactly what people whinge about when his name is mentioned, and that it has probably ever been thus since Harrow. This is a shame, since it would have made his beautifully written but bafflingly pointless and aimless book, which claims to deal with something as real and worldly and dirty as status, rather more readable and infinitely more relevant.

As part of my job description I should here tell you what this book is actually about, but I’m afraid I can’t help you there. I can tell you that the blurb says it is a book about the anxiety of being thought “winners or losers, a success or a failure”, that it is neatly divided into two sections, one entitled “Causes”, with appetising chapter titles such as “Lovelessness” and “Snobbery”; and “Solutions” with chapters titled “Art”, “Christianity” and, of course, “Philosophy”, and that it has lots of illustrations. But I can’t for the life of me say what it all amounts to. I’m not too troubled by this though: if the professional thinker Mr de Botton hasn’t taken the time to figure it out, why should I?

All the same, Status Anxiety is not without rationale. It seems to be a pretext for de Botton to witter on about almost anything that takes his charming fancy and share his wide reading and impeccable tastes with the less fortunate. Status Anxiety parades, ever so benignly, his status and the reader’s anxiety. Occasionally he has something to say rather than report, such as the insight: “Rather than a tale of greed, the history of luxury could more accurately be read as a record of emotional trauma.” Well yes, but who would be interested in reading it?

It’s difficult not to overlook the irony that one of the few commodities that money isn’t supposed to buy is “wisdom”, and that this is the very commodity that Alain de Botton is in the market to sell. I suspect that there is another level of irony here, that part of what people buy when they buy de Botton is the smell of an expensive education, the aroma of a well-stocked library and the time and security to enjoy it, a life relatively free of the material anxieties that plague most people. A life free of the anxieties of, well, life. Readers of de Botton don’t aspire to be wealthy, which would be vulgar; they aspire, much like my writer friends who resent him, to be born to money; to be post-money. “The consequences of high status are pleasant,” writes de Botton. “They include resources, freedom, space, comfort, time and, as importantly perhaps, a sense of being cared for and thought valuable.” You could replace the words “high status” here with “money” and not change the sense of that sentence – and in fact make it rather more sensible.

The book itself is a gorgeously produced item: the luxurious paper, the recumbent white space, the richly redundant illustrations (aristocratically illustrating something from the text that didn’t need to be said, let alone illustrated). It is eminently desirable. The inside jacket copy tells us that

“every adult life is defined by two great love stories. The first – the story of our quest for sexual love – is well known and well-charted. The second – the story of our quest for love from the world – is a more secret and shameful tale.”

In other words, the publisher wants us to think that Status Anxiety is sexier than sex.

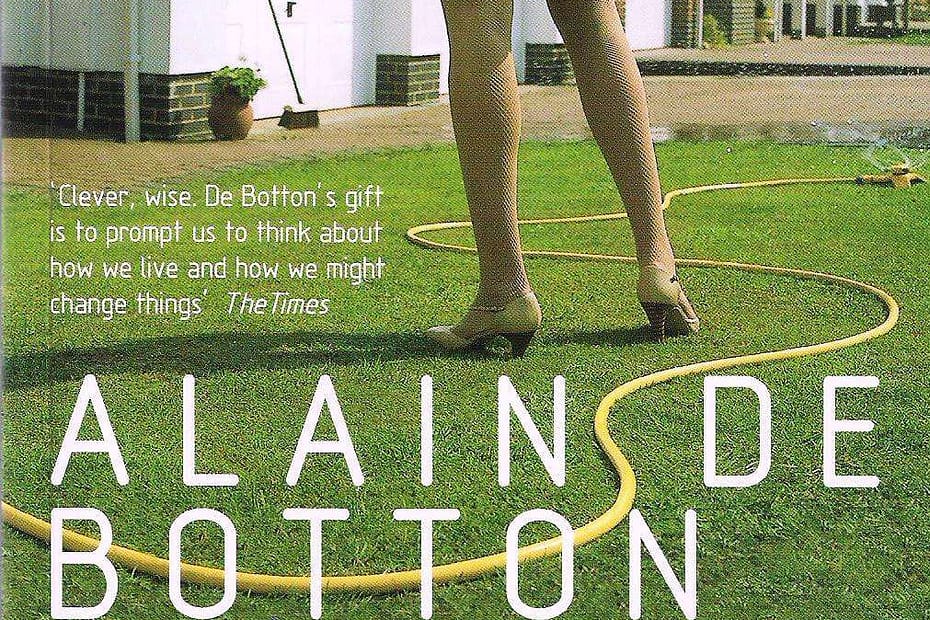

So the cover features a tall skinny lady in high heels and miniskirt holding a shiny and sharp-looking trowel behind her back. Alain de Botton’s name appears next to the shapely shins, and you find yourself wondering if it is him in drag (the lady is headless). Alain/Elaine is standing over a fat yellow garden hose that is ejaculating water over the well-kept moneyed suburban lawn; the hose snakes saucily (desperately?) across the inside cover and across the rear jacket and rear inside cover. Clearly the publisher doesn’t believe for a moment that status anxiety is a sexier subject than sex and is instead frantically trying to sell us subliminally a book about castration anxiety.

Perhaps, as the reactions of my resentful scribbling pals – and my own uncouth review – illustrates, being born to a wealthy father can be rather castrating; how to assert your own status in a world where most things and values, as de Botton admits, are now bestowed by money? What is left in the way of achievements for you to acquire? Well, you could always try becoming a popular philosopher….

But I can’t leave you without mentioning the endearingly silly graphs and tables of blindingly brilliant banality. My favourites are two graphs on p.207 titled “How we imagine satisfaction after an acquisition or achievement” and “What in fact happens after an acquisition/achievement”. The first shows a steep, surging rise in the level of happiness over time which then levels off; the second shows a steep rise followed by a precipitous, drooping fall.

This latter image may or may nor be an accurate plotting of the impotence of worldly goods to satisfy, but it is an entirely accurate and scientific depiction of the effect of buying Status Anxiety.

UPDATE August, 2009

Alain de Botton bites back:

Sorry to be first in line for pedant’s corner, but it was James Wilby (not Peter) who played Maurice Hall in the Merchant Ivory film.

M

Comments are closed.